Well, I was young and hungry and about to leave that place

When just as I was leavin', well she looked me in the face

I said "You must know the answer."

"She said, "No but I'll give it a try."

And to this very day we've been livin' our way

And here is the reason why

We blew up our TV, threw away our paper

Went to the country, built us a home

Had a lot of children, fed 'em on peaches

They all found Jesus on their own

When just as I was leavin', well she looked me in the face

I said "You must know the answer."

"She said, "No but I'll give it a try."

And to this very day we've been livin' our way

And here is the reason why

We blew up our TV, threw away our paper

Went to the country, built us a home

Had a lot of children, fed 'em on peaches

They all found Jesus on their own

Excerpt from “Spanish Pipedream” by John Prine

To me, so many people today who claim to be religious – especially Bible-thumping, God-fearing Christians -- are very judgmental towards others who have even slightly differing belief systems. I see many so-called “religious people” making judgments not only about everyone's religious tenants but also about seemingly every issue affecting modern life.

I find many religions having zero tolerance for accepting anything but their own denominational beliefs. They often resort to direct condemnation of those who even question evangelical principles, claiming those with an open mind are Godless individuals.

The American tradition of openness to people of different faiths has historically been one of America's greatest strengths. Father George Washington helped establish a nation where people could be equally free to the practice of their faiths, and he also believed all faiths should be equally privileged in the political arena.

At one time, I think many religious people revered searching for answers by examining all perspectives, acknowledging inconsistencies, and even encouraging others to seek God in their own devout ways. In fact, “arriving” or “coming to faith” used to be respected as largely dependent upon personal inquiry rather than upon force-feeding one view upon a person.

Now, we are a much more religiously diverse nation than ever, but political leaders are apt to use religion to mobilize the powerful white evangelical voting bloc. I believe this has led to a group of Christians who feel they must control freedoms and liberties for all “right-thinking” Americans. Who is being used when one set of religious ideals exerts undue influence in politics?

Meryl Justin Chertoff, director of The Aspen Institute’s Justice and Society Program and an adjunct professor of law at Georgetown Law, says through research we have learned three major axes over religion exist in America today. Chertoff relates ...

- The first is the division of people of faith and non-religious people, or the “nones” as Professor Robert Putnam and David Campbell call them in their landmark book American Grace. (The “nones” are now 35% among millennials in America.)

- The second is the division between the so-called “Big Three” faiths — mainline Protestants, Catholics and Jews — and minority religious groups. (Chertoff includes Judaism in the “Big Three” not because of absolute numbers, but because these are the three faiths, long represented in this nation, that took the lead in Interfaith 1.0 – when liberal faith denominations were able to bridge differences based on shared values.)

- The third is the conversation that takes place (or does not take place) between progressive and conservative sects within a religion—the intrafaith divide. Sometimes, the most bitter divisions are those between co-religionists.

“In 1955, 92 percent of Americans were Protestant or Catholic, and 4% Jewish. Sociologist Will Herberg titled his portrait of religion in mid-twentieth century America 'Protestant-Catholic-Jew' and wrote that to not identify with one of those is 'somehow not to be an American — even when one’s Americanness is otherwise beyond question.'

“Today less than 50% of Americans identify themselves as Protestant, and there is a growing divergence in beliefs between evangelical churches and the mainline Protestant denominations.

“While the most significant demographic change is the growth of disaffiliation, there has been significant growth in minority religious groups. For example, the U.S. Muslim community, tiny in the 1950’s, has grown largely due to immigration trends. There were 1 million Muslims in the U.S. in 1992. That number grew to 2.75 million in 2011, with the total projected to rise to 6.2 million by 2030. Hindus and Buddhists, less than 1% of the US population presently, are 7 and 6% respectively of recent immigrants.

“These statistics are only a snapshot of the emerging religious diversity of our nation. Our religious diversity is both a challenge and an opportunity. How do we feel about this, and how should we feel?”

(Meryl Justin Chertoff. “Principled Pluralism Requires the Courage for Difficult Conversations.” The Aspen Journal of Ideas. July/August 2015.)

Chertoff tells us, “Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists are viewed unfavorably by white Evangelicals, but better by mainline Protestants and Jews; while Catholics, Mormons and Jews are viewed unfavorably by the 'nones.' The sharpest tension is between white evangelicals and the non-religious, particularly atheists.”

But especially since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, many who practice religion call for socially-sanctioned, religiously-motivated bigotry.

According to Chertoff, “Statistics compiled by the F.B.I., anti-Muslim hate crimes multiplied after September 11th, and they have remained five times as common as they were before 2001. Most religiously-motivated hate crimes are against Jews: in 2013, 59 per cent of such crimes were of this type, whereas fourteen per cent were anti-Muslim. But many American Muslims feel that increasingly, they are portrayed as terrorists in the media, and surveys repeatedly find that Americans harbor chillier feelings toward Muslims than toward any other religious group.”

For evangelical believers, it is difficult to bridge with more liberal denominations because the rejection of their views is so elemental to their own self-definition. In fact, there is a need to “agree to disagree” that there are fundamental and unbridgeable differences of faith that we cannot resolve, but that we can work with cooperatively to achieve the common good.

Chertoff asks us to consider this scenario:

My Take

Religious literacy is essential. People do far too little to understand their own convictions to a denomination or to a religious sect. So many assume their faith is right without even knowing basic facts about their own religion while applying their own strict principles to important issues. In fact, how many Americans know much about the differences among the faiths of Protestants, Catholics, and Jews? Possibly more important, how many even care and prefer to accept blind faith of their one view?

Should we know more about religions other than “The Big Three” faiths that are practiced in America? I think it is imperative that we discover more about the dominant beliefs of others when America exerts such influence in places that practice Islam, Hinduism. Buddhism, and other religions. To condemn the manner in which others worship affronts the cores of their societies.

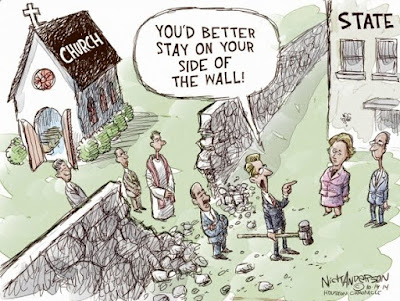

The search for truth and meaning in life as it applies to faith is a noble undertaking. To condemn people for refusing to conform to one set of tenants limits the freedom and liberty that are our precious birthrights. Who wants restrictions on thoughts simply because those thoughts conflict with conventional wisdom? What religion should decide secular matters for all? The need for separation is obvious.

Of course, destructive actions of Jihadists, White Supremacists, or other sects in the “name of religion” must be stopped. These things endanger our country and limit our liberties. It amazes me that people cannot delineate between malformations of faith and Godly adherence. For example, take this growing mistrust of all Muslims supported by many American Christians. Why does such unwarranted hatred spew from true believers when they claim to respect all others with good intentions? Could it be that their agenda is not truly motivated by a loving Creator?

No comments:

Post a Comment