Charles W. Farley

Between 250,000 and 420,000 males under 18 were involved in the American Civil War for the Union and the Confederacy combined.

Given the large number of boys and young men in the American Civil War, compared to the number of older men, one author stated that it "might have been called The Boys’ War." Although the official minimum enlistment age was 18, there were various ways boys got around this – 200,000 were sixteen or under.

(Burke Davis Houhlihan. The civil war: strange & fascinating facts. New York, NY: Fairfax Press. 1982.)

For most young men who survived, the war would never quite be over. It had forced them to endure hardships and to grow up fast enough to take on adult responsibilities. It had shown them just how horrible the world could be. And they would never forget it.

This is a story about a young man – only 16-years-old – who answered the call and became a sergeant in the Union troops during the Civil War. As a soldier and a lifelong resident of Portsmouth, Ohio, Sgt. George W. Farley served his community with unparalleled distinction. His father was born in Virginia, and records don't survive, but you can figure George's slave connections.

One can imagine the determination and drive Farley used to overcome adversity. Many years ago, George's name was chosen to officially honor an important housing project in town. He remains a proud part of the history of our area and state. I hope this brief blog entry opens further exploration of his story and generates more information about one of Portsmouth's finest residents.

George W. Farley was born the son of Jesse Claiborne Farley and Jane (Grant) Farley in Portsmouth, Ohio, on September 25, 1849, in a log cabin at what is now the corner of Kinney's Lane and Franklin Avenue. His siblings include John Farley, Catharine Farley and Franklin Clayborn Farley.

(“George W Farley 1849 – 1940. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Farley-4090.)

George helped his father operate the Underground Railroad.

George Farley served in the American Civil War in Company H 44th Regiment United States Colored Troops. He was only sixteen years-old when he joined the army and was made first sergeant of Company H.

Historical Note:

Recruitment of colored regiments began in full force following the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863. The 44th United States Colored Infantry was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment was composed of African American enlisted men commanded by white officers and was authorized by the Bureau of Colored Troops which was created by the United States War Department on May 22, 1863.

In total, 5,092 Ohio African-Americans served in the USCT. By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war—30,000 of infection or disease.

The 44th USCT was organized in Chattanooga, Tennessee by Colonel Lewis Johnson. Born on March 13, 1841, in Rostock, Prussia, Johnson served as a cadet in the Prussian navy for two years before coming to America in 1855. He enlisted as a private in April 1861, acquiring a commission of captain and wounds from two battles. He was from a family of writers, teachers, and printers, and thus Johnson encouraged his men both white and black to learn to read and write. The 44th regiment also became known as “the singing regiment” thank to the teachings of Rev. Lycurgus Railsback.

The regiment served garrison duty at Chattanooga, Tennessee, until late 1864. They saw battle action in Dalton, Georgia on October 13, 1864. 751 of the 800 regiment men were captured during this fight. 600 of these men, were free African American men, and were part of the largest surrender of African American soldiers during the war.

John Bell Hood’s campaign through North Georgia reached the edge of Dalton, a town his troops were familiar with because they had stayed in Dalton the previous winter. However, Dalton hardly resembled the town they had left when the Atlanta Campaign began: the town was mostly abandoned and had warehouses of supplies. The biggest difference was a garrison composed of a regiment of runaway slaves, the 44th USCT. This was shocking and outrageous to Hood and his men because many of these soldiers were escaped slaves from the North Georgia and Tennessee area.

Late in the morning on October 13th Hood’s Confederate Army of Tennessee approached Dalton and cut off all lines of retreat. The Union defenders which included the 44th USCT under Colonel Lewis Johnson barricaded themselves in Fort Hill. This was an earthen fort built upon high ground east of downtown Dalton. Below them a grim site developed as Confederate artillery deployed on heights across from them, and thousands of infantry filled in the space around.

Confederate General William B. Bate’s and his men were assigned to capture the fort. A message was sent to Colonel Lewis Johnson.

“I demand the immediate and unconditional surrender of the post and garrison under your command, and should this be acceded to, all white officers and soldiers will be paroled in a few days. If this place is carried by assault, no prisoners will be taken. Most respectfully, your obedient servant, J.B, Hood, General.”

According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, Hood vowed to take no prisoners if the Union defenses were carried by assault and later added that he "could not restrain his men and would not if he could."

According to Bate’s records the offer was initially refused. After the refusal, Bate had his men fire several rounds into the stockade and shortly after a white flag was raised. Johnson really had no choice. His garrison of 751 men and two cannons were no match for the 20,000 men and 30 cannons of Hood’s that surrounded them. Colonel Johnson later claimed that his black troops showed the “greatest anxiety to fight,” they did not want to surrender. They knew that capture would bring them great hardships, such as being sold back into slavery or forced into labor for the Confederate army.

After surrender, Johnson secured paroles for himself and the 150 other white troops. The 600 African American men of the 44th USCT were not given the same treatment. At first, they were put to work tearing up parts of the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Private William Bevins of the 1st Arkansas remembered, “The prisoners were put to work tearing up the railroad track. One of the Negroes protested against the work as he was a sergeant. When he had paid the penalty for disobeying, the rest tore up the road readily and rapidly.”

Other cases of abuse occurred, and constant threats were issued forth as the prisoners were forced to move off with the army. Within days, notices were appearing in Southern newspapers announcing the capture of “Negroes” at Dalton—they were never referred to as “soldiers”—and for the owners to come claim them. Some 250 were claimed and most like killed or tortured for having runaway. Of the remaining men a few managed to escape, some simply disappeared, and the rest were taken with the army to do a number of tasks, eventually set to work repairing railroads in Mississippi as the army moved into Tennessee.

By December 1, 1865 only 125 men of the 44th USCT remained alive. The division mustered out of service April 30, 1866. Much remains unknown about the men who would have fought to the death at what we now call Fort Hill in Dalton, GA. We do know they were brave in the face of such hate and ultimately death for many. A plaque has been posted in their honor at the top of Fort Hill. From slavery’s rags to the Union uniform of the 44th United States Colored Infantry.

(“The Brave Men of 44th USCT.” https://www.civilwarrailroadtunnel.com/2021/02/26/the-brave-men-of-44th-usct/. Tunnel Hill Heritage Center and Museum.)

USCT at an abandoned farmhouse in Dutch Gap, Virginia, 1864

Erected by the Georgia Historical Society, the Georgia Battlefields Association and the Georgia Department of Economic Development

Farley was mustered out of service on February 27, 1866, after a full year of service.

At the close of the war, he returned to Portsmouth with honorable discharge. Several years later Farley married Mary Taylor and reared one of the largest families in Portsmouth. The veteran died at March 25, 1940, at the home of a daughter, Mrs. Daisy White and granddaughter, Mrs. Virginia Fox, in Cleveland.

Fraley worked for the Johnson Hub & Spoke Company for 16 years, and he was houseman for Mrs. J.J. Rardin for 25 years. He also worked on river boats from several years.

His wife and he were the parents of 10 children. Records show the following names:

George W Farley (25 Sep 1849 - 25 Mar 1940) m. Mary Taylor (abt Jul 1848)

Frankey Farley (abt 1869)

Jesse Farley (abt 1873)

Clara Farley (09 Sep 1875)

Preston Farley (abt 1878)

Daisy Farley (abt Jun 1879)

George W Farley Jr (abt May 1882)

Raymond Farley (24 Aug 1884)

Lulu Farley (abt Jul 1887)

Florence Farley (03 Mar 1890 - 29 Jun 1968)

Fred Douglass Farley (28 Sep 1892 - 23 Nov 1975)

Wife of George W. Farley – Mary Farley (formerly Taylor)

Born about Jul 1848 in

Virginia, United States![]()

Daughter of [father unknown] and [mother unknown]

[sibling(s) unknown]

Father of George W. Farley – Jesse Claiborne Farley

Born about 1797 in Virginia, United States. He passed away in 1886

Son of [father unknown] and [mother unknown]

Mother of George W. Farley – Jane Farley (formerly Grant)

Born about 1814 in West Virginia, United States

Daughter of [father unknown] and [mother unknown]

[sibling(s) unknown]

(“George W Farley 1849 – 1940. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Farley-4090.)

“With the United States cap on your head, the United States eagle on your belt, the United States musket on your shoulder, not all the powers of darkness can prevent you from becoming American citizens. And not for yourselves alone are you marshaled — you are pioneers — on you depends the destiny of four millions of the colored race in this country . . . If you rise and flourish, we shall rise and flourish. If you win freedom and citizenship, we shall share your freedom and citizenship.”

– Frederick Douglass January 29, 1864, Fair Haven, Connecticut; address to the 29th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry regiment (African descent)

George Farley was a member of the Lucasville Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) until the post disbanded. He participated in Memorial Day events here in 1939. and was the lone Civil War veteran attending the annual celebration.

Historical Note:

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a patriotic organization of the U.S. Civil War veterans who served the Federal Forces. One of its purposes was being the “defense of the late soldiery of the United States – morally, socially, and politically.” But into the earliest hour of well-worn peace after the war, there came the presence of disabled veterans, suffering families, and distressed homes. The aid to these came cheerfully the GAR.

Founded in Springfield, Illinois in early 1866, it reached its peak in membership (more than 400,000) in 1890. For a time, the GAR was a powerful political influence.

Membership declined as veterans died, but as late as 1923, 65,382 members remained. In 1949, six of the surviving veterans met at Indianapolis for the 83rd and last national encampment. In 1956, the GAR was dissolved; its records went to the Library of Congress, Washington D.C. and its badges, flags, and official seal to the Smithsonian Institute.

The GAR was very strong in Ohio. The state encampments attracted thousands of veterans and their supporters. Numerous GAR retirement homes existed in the state. One GAR home became the Ohio Soldiers' and Sailors' Orphans' Home in 1870. The GAR established the home in 1869, and the state government assumed control of it in 1870 to provide Ohio veterans and their children with assistance.

The Ellsworth Post No. 382, Lucasville, Ohio, was chartered September 29, 1883.

(Ohio Dept GAR Archives Ohio Historical Society)

While a flood refugee in 1937, Farley suffered a broken hip (“fractured right thigh”) in a fall on the stops of Lincoln School, and later he was said to have “never really recovered” from the injury.

At the time of his death on March 25, 1940, he reportedly was the oldest person living born in Portsmouth (90 years and six months).

"As a regiment we cannot be excelled, as men, we have only our equals, but as citizens, our motto is, veni, vidi, vici. We came as soldiers, as men we saw and acted upon, and as the noble handiwork of God, we have conquered one-half of the prejudice that has been for the last half-century crushing our race into the dust. And now . . . it affords us, I say us, for I share in common with my poor benighted race, a happy time in thinking that through the instrumentality of an all-wise Providence we are considered, by all that are lovers of the Union and Freedom, freemen."

– Private Jacob S. Johnson, Company H, 25th USCT, January 22, 1865

Also, when George Farley died, he was Portsmouth's last surviving Union veteran. He was buried with military honors in Soldiers Circle at Greenlawn Cemetery

(“Northend Reunion.” Facebook Group. Jan. 28, 2022. From Portsmouth Times. May 04, 1941.)

Much of the information about George W. Farley was generated from an essay contest sponsored by the Portsmouth Metropolitan Housing Authority to name the housing project in the North End. All essays came from students in Washington School, and Principal E.M. Gentry assisted the housing authority in picking the winners.

From nearly 100 suggestions, the PMHA chose eighth-grader Odessa Barrett, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. James Barrett, 1209 Findley Street, as the winner. Her essay submitted the name of George W. Farley Square. Six students had actually chosen George Farley for the honor, but Barrett wrote the most outstanding essay.

As second place winner, seventh-grader Patricia White, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Irvine White, 1034 15th Street, recommended naming the housing project for Mrs. Louise White, active as a leader for civil rights in the area for many years. Patricia's father was employed by the Norfolk & Western Railway.

Please click here to watch a YouTube video of Soldier's Circle Greenlawn Cemetery Portsmouth, OH:

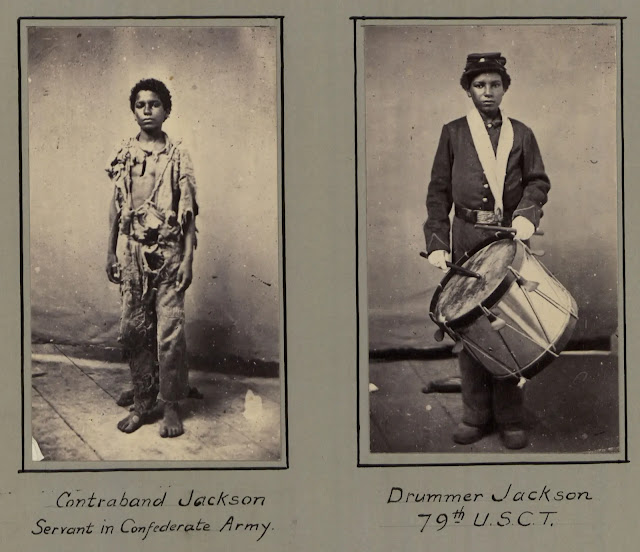

Before and after images

of drummer boy “Jackson”

Photo Source: From Carlisle Military

History Institute via To look like men of war: visual transformation

narratives of African American Union Soldiers; see also here, page 7.

What’s going on here? According to Corbis Images, the boy in the “Portrait of ‘Contraband” Jackson,’ (is) supposed to look like many of the runaway slaves that flocked to the banners of the Union Army during the American Civil War. Used in combination with a photograph of Jackson as a drummer in military uniform, this was circulated to encourage enlistments among African Americans.” Indeed, the photographs make a poignant appeal to the conscience of black men: if a young boy was willing to serve, then why shouldn’t you?

Lucasville GAR Members

No comments:

Post a Comment