Painting from the Ancient Ohio art series depicting a Paleoindian (14,000 BC -7,000 BC) family dressing caribou hides at their camp in western Ohio.

Just how far back have humans inhabited the Scioto River Valley, our beautiful, natural home?

The valley has long been recognized to contain some of the richest, and most spectacular, archaeological deposits within the nation. The prehistory and history of the Scioto Valley rivals that of any American location. A novice expecting to find the first people here to be members of Native American tribes like the Shawnee will be surprised to discover just how far back humans roamed the area.

Today, my blog entry represents a timeline of the settlement of the Scioto River Valley. Many thousands of years before the Europeans – those groups of pioneers like French traders and English settlers – others made their home here. Thanks largely to research by the Department of Energy, I want to trace briefly the long history of this very special place, and in this entry, focus specifically on what we know today as Pike County.

I hope you find something new and interesting here. Don't forget to dig more yourself and pass it on. Local history is amazing. Our youth need to know the story of their blessed environment.

Also, please take the time to read the entire DOE reference by clicking here: http://portsvirtualmuseum.org/.

(You may wish to begin with “Pre-Historic Archaeology of the Portsmouth Site 10,000 BC to 1500 AD.” PortsVirtualMuseum.org. Operated and managed by Fluor-BWXT Portsmouth for DOE.)

Paleoindian Period

Science reveals some incredible support that people may have been here 13,000 years ago. PortsVirtualMuseum.org and the Department of Energy report that the earliest clear evidence for Native American utilization of the Midwest is represented in the Paleoindian Period (about 13,000 to 7000 B.C.) – marked by the retreat of the last glaciers and characterized by a warming climate and the development of hardwood forests.

By the way, this is long before the Adena and Hopewell inhabitants with whom we are much more familiar.

How did these early people get to Ohio? Traditional theories suggest that big-animal hunters crossed the Bering Strait from North Asia into the Americas over a land bridge (Beringia). From c. 16,500 – c. 13,500 BCE (c. 18,500 – c. 15,500 BP), ice-free corridors developed along the Pacific coast and valleys of North America. This allowed animals, followed by humans, to migrate south into the interior of the continent.

During the Paleoindian Period, small groups of hunting and gathering people lived on the landscape in a highly mobile fashion; it is estimated that the entire State of Ohio likely housed less than 700 people at this time. Early Paleoindians hunted now extinct species of big game animals such as mammoth and mastodon. Mastodon or mammoth bones have been found in nearly all parts of Ohio. The Burning Tree mastodon was excavated from a bog in southern Licking County. Some of the bones had been cut, possibly by stone tools when Paleoindians butchered the animal.

The Paleoindians also hunted deer and small game, fished, and gathered nuts and fruit when available. One of their most important natural resources was flint. Tools made from flint supplied them with all they needed to live.

(Mark F. Seeman, Garry L. Summers, Elaine Dowd and Larry L. Morris. Fluted Point Characteristics At Three Large Sites: The Implications For Modelling Early Paleoindian Settlement Patterns In Ohio. 1994.)

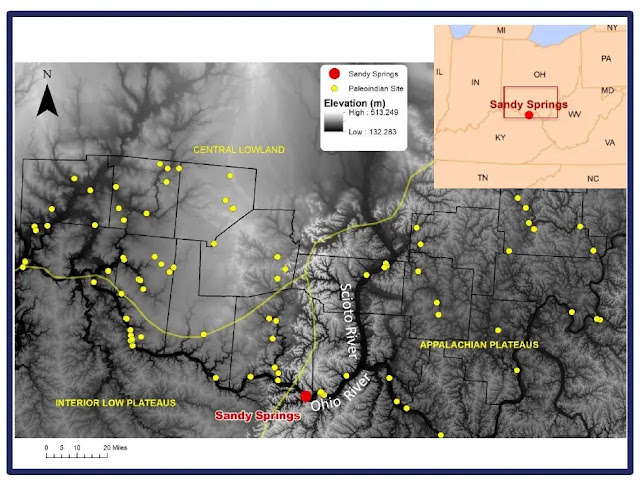

Although most of Ohio’s studied Paleoindian Period sites are located in the state’s northeast quadrant, the Sandy Springs site is situated on the Ohio River near the confluence of the Scioto River.

Sandy Springs is a large site whose occupants crafted the time period’s distinctive lanceolate and fluted lanceolate shaped projectile points during repeated visits over a time span of approximately 1500 years.

Sandy Springs has produced large numbers of the prolific and diagnostic Paleoindian projectiles known as fluted points. It has been estimated that over 1000 of these Clovis-like points have been found in Ohio, a density second only what has been found in Alabama.

Roger Cunningham, an insurance salesman from Rock Run’s Buena Vista, first wrote about Sandy Spring’s artifacts back in 1973. Many of the Paleoindian points he studied are still in the stewardship of local residents whose ancestors collected them on the sandy surface of their agricultural fields.

The high density of projectile points at Sandy Springs indicate that a relatively high concentration of indigenous peoples gathered in the sandy flats along the Ohio River during the Paleoindian era, presumably to hunt, but perhaps for other reasons as well.

(Matthew P. Purtill. “Sandy Springs Region of Rock Run.” The Arc of Appalachia. arcofappalachia.org.)

Early Archaic Period

The Early Archaic Period (8000 to 6500 B.C.) was marked by continued warming and a transition to hunting woodland animals such as deer, rabbits, passenger pigeons, and wild turkey. Early Archaic groups still lived in smaller groups and were highly mobile, but population densities appear to rise dramatically by the end of the period.

Early Archaic peoples also gathered berries, hickory nuts, and acorns. Growing populations and new food sources led to technological changes, especially a wider array of spear point types that may have had social significance.

Middle Archaic Period

The succeeding Middle Archaic Period (6500 to 4000 B.C.) is poorly understood. Based on a review of existing material, and radiocarbon dates, scholars suggest that this period witnessed significant population reduction, perhaps by as much as 80 percent. The reason for this depopulation is unclear, but environmental evidence suggests that considerable variation in climatic conditions could have resulted in unpredictable resources from year-to-year, making the Ohio region unattractive for habitation during this time.

(Matthew P. Purtill. “The Road Not Taken: How Early Landscape Learning and Adoption of a Risk-Averse Strategy Influenced Paleoindian Travel Route Decision Making in the Upper Ohio Valley.” Cambridge University Press. December 30, 2020.)

During the Middle Archaic period, Midwestern Archaic cultures evolved into societies of great complexity and created stone artifacts of elaborate and unique design, the finest examples of which are found in Ohio. Evidence shows Middle Archaic peoples crafted a diverse range of spear points, knives, and scraping tools, as well as grinding tools like grooved axes, atlatl weights, grinding stones, pitted stones, plummets, and net sinkers.

Late Archaic Period

By around 4000 B.C., or the start of the Late Archaic Period (4000 to 700 B.C.), environmental conditions stabilized and the climate assumed modern conditions. Woodland game thrived and forests of nut-bearing trees such as hickories, black walnuts, and oaks rapidly expanded throughout central and southeastern Ohio.

Archaeological investigations at the Madeira Brown site, situated on a terrace of the Scioto River just north of Portsmouth, provide extensive evidence of nut and squash utilization by Late Archaic groups.

(Thomas E. Emerson (Editor), Dale L. McElrath (Editor), Andrew C Fortier (Editor). Archaic Societies: Diversity and Complexity Across the Midcontinent Illustrated Edition. 2009.)

These conditions were very favorable for hunter/gatherer societies and archaeological evidence suggests substantial population increases first in the southern part of the state and somewhat later in the north. The Late Archaic witnessed intensification of subsistence strategies engaged in during earlier times, especially the collection of wild plant foods and the practice of incipient horticulture.

Crops were grown in gardens, but not as intensively as with cultures of the Early Woodland period (2,800-2,000 BP). In conjunction with pottery production, the incorporation of growing crops – sunflowers, sumpweed, and squash – suggests that these people started to establish seasonally permanent villages. Still others believe late Archaic people moved to different sites according to the seasons. Crops were probably small additions to their diet.

Many Late Archaic funerary objects were made from resources not native to Ohio, suggesting an increased importance in materials from different places. Examples include flint from Indiana, copper from the Lake Superior region, and shells from the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast. Some archaeologists speculate that Late Archaic groups held shamanistic beliefs, as suggested by these funerary objects which appear to have been sacred or important in some way, possibly a shared belief system with American Indian groups.

(“Late Archaic Culture.” Ohio History Central. ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Late_Archaic_Culture.)

Early And Middle Woodland Periods

In Southern Ohio, more evidence of year-round occupation of sites is found, indicating increased sedentism and greater population across the state. Some of the most dramatic Native American building projects in the Midwest occurred in the Early Woodland Period (700 to 100 B.C.) and the succeeding Middle Woodland Period (100 B.C. to A.D. 500). These periods witnessed the height of the “Moundbuilders Culture,” which was characterized by the construction of earthen burial mounds and geometric earthworks. The density of mounds and earthworks in the Scioto Valley attracted the attention of many early professional archaeologists.

The Adena Culture of the Early Woodland Period is the best known Early Woodland complex in the area. The burial mounds associated with this cultural manifestation are typically small, and are usually located on either high terraces or bluffs or within the valley bottoms.

(John Waldron and Elliot M. Abrams. “Adena Burial Mounds and Iner-Hamlet Visibility: A GIS Approach.” Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 24, No. 1. Spring, 1999.)

Because of their distinct appearance on the landscape, Adena mounds have long been the subject of archaeological investigations. In Pike County, the largest mounds are Adena mounds and many of them are located near the Portsmouth DOE facility. These well-documented, though mostly non-extant, resources include Graded Way Mounds, Van Meter Mound, Vulgamore Mound, and Barnes Mound, to name a few.

Adena habitation sites, on the other hand, are usually small villages or hamlets located along low terraces and in the floodplains of stream valleys. Prufer (1967:315–316) noted little Early Woodland material during his Scioto Valley survey, which was especially interesting given the valley’s abundance of Adena burial mounds.

(Olaf H. Prufer. "How to Construct a Model: A Personal Memoir," Chapter 4 in Ohio Hopewell Community Organization, William S. Dancey and Paul J. Pacheco, Editors. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1997.)

During the Middle Woodland Period, Native Americans continued to be involved in mound and earthwork construction. In Ohio, the Middle Woodland Period is often called Hopewell. This period was characterized by elaborate geometric earthworks, enclosures, and mounds that are often associated with multiple burials and a wide array of exotic ceremonial goods.

Unlike the Adena, the Hopewell did not bury their dead in the mounds. Instead, almost all Hopewell mounds cover the place where a building used to stand. One of the more famous of these in the lower Scioto River Valley was found at the Tremper site, which consists of a low embankment encircling a large mound covering the remains of a multi-chambered building. Tremper is located on the west side of the Scioto River about five miles northwest of Portsmouth.

(Jarrod Burks, Ph.D. “Prehistoric Native American Earthwork and Mound Sites in the Area of the Department of Energy Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant, Pike County, Ohio.” Ohio Valley Archaeology, Inc. September 2011.)

Some of the more notable Middle Woodland complexes are located in the Scioto Valley, near Chillicothe, and they include Hopewell Mound Group, Mound City Group, High Bank Works, Seip, and Harness.

(Brad Lepper. “Hopewell Culture.” Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. November 2017.)

Near the Portsmouth DOE facility, the Seal Township Works and the Piketon Graded Way are two of the most prominent earthwork complexes in Pike County. Materials used in the manufacture of these ceremonial items were acquired from various regions of North America, including the Atlantic and Florida Gulf coasts (shell, shark and alligator remains); North Carolina (mica); the southern Appalachians (chlorite); and Lake Superior (native copper); meteoric iron was also recovered from several sources. Ceramic assemblages are characterized by a range of domestic and ceremonial types, including plain, cordmarked, and decorated types, many of which appear to have been influenced from outside sources (to the south).

Many Hopewell earthwork complexes seem to incorporate smaller Adena enclosures and mounds, suggesting that the Adena and the Hopewell are not simply different cultural groups. Rather, they shared an ancestor/descendant relationship during a time of rapid cultural change in some valleys, especially the Scioto.

(Nomi B. Greber. “A

Study of Continuity and Contrast between Central Scioto Adena

and

Hopewell Sites.” West Virginia Archeologist

43. 1991.)

Life-size figure executed for the Ohio State Museum--the first known attempt to scientifically portray the builders of the ancient mounds as they appeared in life. This image was taken from Henry Clyde Shetrone's book The Mound-Builders, copyright 1930. Ancient Architects of the Mississippi

Piketon Mounds

The Piketon Mounds are a grouping of four conical burial mounds preserved in Mound Cemetery in Piketon, Ohio. The largest of the mounds is about 25 feet high and 75 feet in diameter. The smaller mounds range in height from five to two feet.

This mound group is associated with a "Graded Way," or set of parallel embankments that frame a natural drainage channel that leads from the high terrace down to the Scioto River.

The age of the Piketon Mound group is unknown. Such groupings of conical burial mounds are typical of the Adena culture (800 BC – AD 100), but the parallel embankments framing the "Graded Way" are more typical of the Hopewell culture (100 BC – AD 500).

These mounds were first documented formally by Caleb Atwater (1778 – 1867) in 1820, who recorded several sites within the Scioto Valley including the Piketon Earthworks (33PK1) located on the southern banks of the Scioto River near present-day Piketon. During his professional career, Atwater held positions of a teacher, a minister, a State Representative, a Postmaster, and a lawyer.

At the time, Atwater and other scholars developed various theories of origin; he thought a culture other than ancestors of Native Americans created such monuments. He helped publicize a theory by John D. Clifford, an amateur of Lexington, Kentucky, who suggested that people related to Hindus of India had migrated by sea and built the mounds, to be replaced by ancestors of more warlike, contemporary Native Americans, who had driven the moundbuilders south into Mexico.

Atwater believed that “a superior race had built the mounds,” and concluded “that American Indians were not mentally capable of such tremendous architectural feats.” His views remained prominent among scholars for several decades.

(John D. Clifford, Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, Dr Charles Boewe, PH D. John D. Clifford's Indian Antiquities. 2000.)

The following is taken

from Atwater's Descripton of the Antiquities

Discovered In the State of Ohio and Other Western States

communicated to the president of the American Antiquarian Society in

1820:

“Besides those above mentioned, there are parallel walls in most places, where other great works are found. Connected with the works on Licking Creek, are very extensive ones, as may be seen by referring to the plate which represents them. They were intended, I think, for purposes of defence (sic), to protect persons who were travelling from one work to another. The two circular ones at Circleville were walls of the round fort. There are many others in various places, intended for similar purposes. But I am by no means sure, that all the walls of this description were intended as defensive; they might have been Used as fences in some places, or as elevated and convenient positions, where spectators might have been seated, while some grand procession passed between them.

“Near Piketon, on the Scioto, nineteen miles below Chillicothe, are two such parallel walls, which I did not measure, but can say without hesitation that they are now twenty feet high. The road leading down the river to Portsmouth, passes for a considerable distance between these walls. They are so high and so wide at their bases, that the traveller would not, without particular attention, suspect them to be artificial. I followed them the whole distance, and found that they lead in a direction towards three very high mounds, situated on a hill beyond them. It is easy to discover that these 25 walls are artificial, if careful attention is bestowed on them. It is easy to discover that these walls are artificial, if careful attention is bestowed on them.

“Between these parallel walls, it is reasonable to suppose processions passed to the ancient place of sepulture; and what tends to confirm this opinion is, that the earth between them appears to have been levelled by art. On both sides of the Scioto, near these works, large intervals of rich land exist; and, from the number and size of the mounds on both sides of this stream, we may conclude that a great population once existed here.

“Such walls as these are found in many places along the Ohio, but they generally lead to some lofty mounds situated on an eminence. Sometimes they encircle the mound or mounds, as will be seen by referring to some of the drawings in this volume; others are like those near Piketon. (See the Plate.)”

“Path Of Pilgrimage” Historical Note:

33Pk6 (sometimes also referred to as

the Scioto Township Works II) is located along the U.S. Rt. 23

northbound off-ramp on the east side of U.S. Rt. 23-at the west

entrance to the DOE facility. However, the exact location of this

site was only recently re-established

(Burks 2006 and GIS

specialist Mark Kalitowski independently re-discovered the site

at

about the same time).

Prior to 2006, the site was positioned in the wrong location on the OAI maps. But this inaccuracy was rectified after the earthwork was re-identified in early aerial photographs of the area.

In his book Hidden Cities, Roger Kennedy (1994:57) matter-of-factly refers to this earthwork as a "herradura," or a wayside shrine along a path of pilgrimage. In this case, Kennedy's path of pilgrimage runs from the Chillicothe area south along the Scioto River to Portsmouth.

While ancient paths of various configurations and courses no doubt existed along the Scioto, and these likely changed over the millennia, we have no indications that one ever went through 33Pk6.

Even when the earthwork is very clearly visible in 1934 and 1938 aerial photographs, there is no sign of any pathway or embankment walls leading up to or away from the 33Pk6 gateways. While long lines of parallel embankments are present at the Newark Earthworks, and have been the source of much discussion surrounding the existence of a "Great Hopewell Road" running between Newark and the Chillicothe area (e.g., Lepper 1996,2006), this postulated, formal road has not been traced into the Lower Scioto Valley.

Of course, this does not preclude the possibility of there having been a formal trail linking the earthwork-rich area at Chillicothe with its southern neighbors at the Seal Township Works and Portsmouth. But, such a linkage must consider the age of all of these earthworks for not all of them were present or in use at the same. This latter distinction is an important one.

The mere presence of an earthwork on the landscape does not mean that it was actively being used at a given time in prehistory. Quite a few small enclosures, of the size of 33Pk6, if not the exact shape, were built in the few hundred years before the existence of the Seal Township Works and the "Great Hopewell Road" and they had been "abandoned," in the sense that they were no longer being used, by the time the Seal Township Works were built. Dating the construction and use-period of an earthwork, to a small period of time (e.g., a 1OO-year period), is a very difficult archaeological task.

(Jarrod Burks, Ph.D. “Prehistoric Native American Earthwork and Mound Sites in the Area of the Department of Energy Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant, Pike County, Ohio.” Ohio Valley Archaeology, Inc. September 2011.)

Barnes House

The Barnes House is located just off of US Route 23 in Sargents. It is a historic but abandoned residence once-occupied by a well regarded and politically connected family in Ohio.

After Joseph Barnes, a well-regarded Virginian who co-invented the steamboat, lost a patent dispute in the state legislature, he migrated his family to Scioto County, Ohio. Between 1803 and 1805, the family constructed a stately Georgian residence south of Sargents (today’s Piketon) within the fertile Scioto River valley. The house was Masonic-inspired and featured a pyramid-on-cube shape.

Joseph, a prominent Freemason, frequently rubbed shoulders with various notables, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson worked with Barnes personally to revise the new patent law when he was Secretary of State under Washington.

(Eric Wrage. “A Pike County Gem: The Barnes Home.”News Watchman. March 29, 2019.)

(“Barnes or ‘Seal Township’ Earthworks.” The Ancient Ohio Trail. 2017.)

John Barnes Jr., of the family, founded the Party of Henry Clay in Pike County. And, the Barnes Home served as a center for progressive politics in southern Ohio. Henry Clay himself, and the famous archaeologist Ephraim Squier were regular guests.

In 1900, the last passenger pigeon ever seen in the wild was mounted and displayed in the house, then occupied by the former Pike County sheriff, Henry Clay Barnes and his wife, Blanche, who died as a likely result of arsenic poisoning from her taxidermy.

Here is an interesting connection that links Abraham Lincoln, the Piketon mounds, and Joseph Barnes …

In 1848, as he was ending his last term in Congress, Abraham Lincoln stayed over at the Barnes residence. Lincoln, returning from Illinois to Washington via a steamboat up the Ohio River from St. Louis, had become interested in the Native American earthworks in the area after reading Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley by Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis.

The future president was specifically interested in the Barnes stately brick residence as it aligned on a cross-axis with Seal Township earthworks, which contained a perfect circle and a square, the only major geometric earthwork aligned north-south. (This square is the only one known to have aligned with the cardinal points, its gateways opening due north, south, east, and west.)

(https://abandonedonline.net/location/barnes-house/)

It became clear that Lincoln was fascinated with the different sites Squier and Davis described. If you look at his route, he would have had the opportunity to visit many of the sites described by Squier and Davis, including the Portsmouth works, and the works that were in front of the Barnes' house. Lincoln stayed at the Barnes residence on his visit. Much of the site is now largely lost to gravel quarries.

Early European Settlers

Hezekiah Merritt is given credit with planting the first crop of corn in the area. He came to what is now Pike County in December 1795, constructing a crude log cabin near the present location of Wetmore in the extreme southern portion of the county.

After government surveyors entered Southern Ohio after the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, Mr. Merritt was forced to move, he having no title of ownership to the Congress Lands. He and his family purchased lands across the river from an owner of Virginia Military District property and settled in present Camp Creek, where the Merritt Family Cemetery can still be visited today.

As the first pioneer settler of Camp Creek Township. Merritt was a millwright as well as a farmer. He built a grist-mill at the head water of the Scioto River. He accumulated over 300 acres. His home was a big two-story log cabin with fire places on either end of the house – both floors.

Following the organization of Pike County, Merritt performed the first recorded marriage serving as Justice of the Peace on May 04, 1815. He moved to Bond County, in the 1840's. His stone shows he died Jan 1, 1859, age 91. His & his son's last name is spelled Merret in the cemetery, but grandchildren were spelled Merritt.

If my math is correct, Hezekiah Merritt is the fourth great-grandfather of my wife, Cynthia Johnette (Merritt) Thompson.

Other early settlers of Pike include the Chenoweth brothers (Arthur, John and Abraham) who, along with John Noland, who established a settlement near the present location of Piketon in 1796. While it is impossible to list all the early pioneers in Pike County, a representative listing follows:

John Kincaid

John Parker

Ezekiel Moore

Joseph, George, and Isaac Peniston

Snowden Sargent

James Sappington

William Beekman

Daniel Daily

Presley Boydston

George Steenberger

John Barnes

William S.D. Wynn

John Satterfield

Rev. William Talbott

John Guthery

No comments:

Post a Comment