“As

John Morgan and his band are now captured, the people can settle down

and content themselves with a least of hope that one horse-thieving

scoundrel and disturber of the peace of the county, will get his just

deserts. If our people don’t shoot him for the raid, the rebel

authorities will be sure to, if they ever lay hands on him. He has

wasted and destroyed, on a fool’s errand, the best body of cavalry

they had in their service, and all to no purpose in the world. Such a

senseless expedition never started since the world began. He has

failed to perform a single achievement that is worth thinking of a

second time.”

Newspaper

account of Morgan’s Raid – Cambridge Times,

July 30, 1863

Seldom has any movement aroused such intense excitement and bitter feelings as did Morgan's raid into Indiana and Ohio during the Civil War. As evidenced by the account above, to the North, Morgan was a bloodthirsty ruffian. But, to the South, he was a brave and daring hero.

General John Hunt Morgan's raid into Indiana and Ohio really had little or no influence on the outcome of the Civil War. Although it was made to injure the Union cause, it stoked feelings of loyalty in residents who were staunchly bound to the Union

It is recorded that Morgan's theory of waging war was to go deep into the heart of the enemy's country. He had sought long and earnestly for permission to put this theory into practice. A raid into Ohio had long been his fondest dream, and, about the middle of June, 1863, upon his arrival in Alexandria, Kentucky, the golden opportunity seemed to lie before him. The situation in Tennessee was daily growing more pressing for the Confederate armies there. It was soon evident that some solution for their problem must be found.

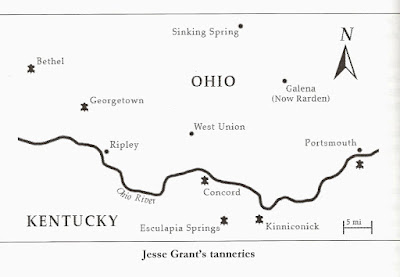

Into Southern OhioFrom July 13-26, 1863, Confederate Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan led a daring group of more than 2,000 men across Southern Ohio. His mission: to distract and divert as many Union troops as possible from the action in Middle Tennessee and East Tennessee. Union troops under the command of Major General Ambrose Burnside gave chase.

During his daring raid, Morgan and his men captured and paroled about 6,000 Union soldiers and militia, destroyed 34 bridges, disrupted the railroads at more than 60 places, and diverted tens of thousands of troops from other duties.

More than 200 northern lives were lost in the two week period of the raid into Ohio with at least 350 casualties. 4,375 people in twenty-nine counties filed claims for damages and were awarded $428,168. The Union forces were also charged with damages totaling $141,855, the militia being held accountable for $6,202. Upwards of 2,5000 horses were commandeered and collected by Morgan. There were 49,357 militia men called to duty costing the state $450,000. The cost to the state was more than $100,000.

The biggest impact on Ohio at the time was the realization that they were truly unprepared for the war to be in their own "backyard.” They had felt secure by the distance from the south and had not put much effort into preparations for defense. The fact that Morgan was able to almost traverse the whole state, from Harrison in the west to West Point in the east (only about 10 miles from Virginia (West Virginia) and Pennsylvania, with little or no resistance is testimony to this fact.

In West Point, Ohio, there stands a stone monument to the events of July 1863. It was erected in 1909 by Will L. Thompson of East Liverpool. It states:

"This stone marks the spot where the Confederate raider General John H. Morgan surrendered his command to Major General George W. Rue, July 26, 1863, and this is the farthest point north ever reached by any body of Confederate troops during the Civil War."

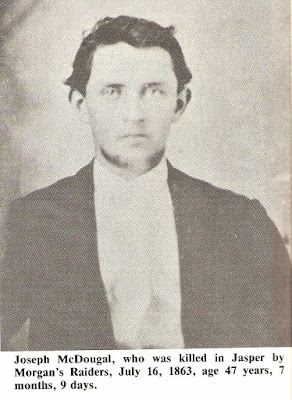

The Account of the Local RaidHere is a written account of the raid near and in Jasper, Ohio. It begins on Thursday, July 16, 1863, and is taken in its entirety from Morgan’s Raid Across Ohio: The Civil War Guidebook of the John Hunt Morgan Heritage Trail published by the Ohio Historical Society on November 20, 2014 by Lora Schmidt Cahill and David L Mowery. It is offered here in memory of local resident, Joseph McDougal, who, in giving his life that fateful day, entered into the annals of history.

“The raiders began to move out of Locust Grove shortly after dawn. A small party moved southeast to Rarden in Scioto County as a feint on the city of Portsmouth. The main force moved northeast.

“Three men who were too ill to ride were left behind. The Platter family cared for them until they were able to travel. When they reached their homes in the South, they wrote to their hosts, thanking them for the hospitality they had provide.

“Edward L. Hughes was a well-respected and prosperous local farmer. He was especially proud of his fine horses. When Duke's men appropriated two of them, he appealed to General Morgan for their return. When that failed, he volunteered to serve as Morgan's guide to Jackson, hoping to recover the horse.

“On reaching Jackson, Hughes, a large Irishman, became drunk and boisterous. Morgan dismissed him. Not only did Hughes fail to recover his horses, but when Hobson (Brigadier General Edward H. Hobson) arrived, Hughes was arrested and sent to jail for treason. Out on bail, he fled to Montreal, Canada. After Lincoln's Amnesty Proclamation in 1863, Hughes returned to Locust Grove and took the loyalty oath. He soon discovered that he was no longer welcome in Adams County; he left the area and moved west.

“In 1863, most of Morgan's men used a road that no longer exists; known as the Chillicothe Road, it ran northeast from Hackelshin Road to the Poplar Grove Road. Morgan used the Chillicothe Road instead of the Piketon Road in order to deceive Federal authorities into thinking he intended to attack Chillicothe. This feint worked well.

“A small company of scouts rode up Union Ridge and around to Smith Hill.

“The Kendall farm was locted between Poplar Grove and Arkoe. The raiders took fresh bread from Mrs. Kendall's oven. Near Arkoe, the raiders took Lewis Beekman't horse and 20 pounds of honey from his hives.

“On Chenoweth Fork Road, a large two-story house was the William Henry home. It served as a station on the Underground Railroad.

“Mr. Henry took his livestock to the woods. Not intimidated by Morgan's men, his sixty-six-year-old wife, Jane, drove the raiders out of her house and flower beds with a broom stick. After they showed the respect due her, she fed them and let them water their horses in the creek behind the house. She then requested and received a receipt for her services. When the captain was writing the receipt, another raider slipped into the barn and took a saddle, four bridles, two halters, and a horse blanket. When Mr. Henry returned home, he was not impressed with his wife's account of her dealings with the raiders.

(The original junction of Chenoweth Fork and Tennyson roads was lost when SR 32 was improved.)

"Morgan's men became frustrated by the number of trees felled across the roads. Governor Tod had called forth the axe brigades of southern Ohio, and they were responding. Downed trees were not a major problem for the riders, but they delayed the wagons and artillery pieces.

“Near Tennyson, Benjamin Chestnut, his brother, and his son Isaac had just felled a tree across the road, at a spot where the road dropped off on the left side.

“Confederate scouts, hearing the tree fall, hurried ahead, captured the local “woodsmen,” and ordered the trio to cut up the tree. One of the rebels gathered up the men's horses while another confiscated Benjamin's money pouch. The three dismounted axemen climbed to the top of the hill and watched as Morgan's main column rode by them.

“At Sunfish Creek, the Stewart Alexander mill and residence were located downstream on the right.

“Two of the miller's older sons were ordered to help clear downed trees from the road.

“Three of the younger children had gone berry picking and returned home to learn that Morgan's raiders were approaching. The younger children were sent to hide in nearby woods, while their parents remained to face the intruders. One of the boys made it no farther than the chicken house. A raider opened the door but did not discover him. The raiders broke into the mill and took all the wheat flour and cornmeal. They opened the grain bins and fed their horses.

“When the children returned home from the woods, the raiders were gone, and so were their berries. Alexander lost a barrel full of honey from the cellar, his gun, and one of his horses to Morgan's men.

“The raiders crossed and burned the nearby 125-foot covered bridge over Sunfish Creek. Some accounts credit the raiders with burning the mill. However, an account written by Alexander's granddaughter, Lina Silcott Shoemaker, refutes the claim. She wrote that as soon as the raiders left, Alexander collected corn and wheat from the neighbors and started milling. He knew his customers would need flour and meal to replace that lost to the raiders.

“Morgan sent a company right on Long Fork Creek Road. The men passed over Yankee Hill and followed Long Fork toward the Scioto River.

“Near the crest of Stoney Ridge on Jasper Road, valiant men made their stand.

“News of Morgan's approach reached Jasper several hours before the raiders arrived. Andrew Kilgore was chairman of the Pike County Military Committee. He was assisted by Jasper storekeeper, Samuel Cutler. The committee was responsible for recruiting in the area and for the defense of the county in an emergency.

“Some of the Pike County Volunteer Militia had been called to Camp Chase to help protect Columbus; other members were sent to aid in the defense of Chillicothe and Portsmouth. The militia was fully armed and counld be called up at an hour's notice by the governor. It would later become the National Guard.

“The home guard could be called out only to defend their local area in case of attack. On July 16, it fell to Kilgore's men to protect Jasper. Kilgore chose a spot on Stoney Ridge, about four miles west of Jasper, for the construction of a barricade. From here, the forty citizen-soldiers would have a clear field of fire down the road.

“The town's doctors, lawyers, clerks, and clergymen had joined farmers and laborers behind the barricade. The nervous men waited for Morgan's charge. They were prepared to defend their town even though outnumbered four to one.

“Morgan's scouts arrived about 1:00 p.m. They notified him of the barricade. Morgan realized that he would probably lose men in a direct charge. He ordered several companies of the Second Brigade to dismount and fire a volley at the barricade.

“The surprised defenders were not expecting the dismounted attack. After firing several rounds, they surrendered. (It took Morgan six hours to get past this defended obstacle.) The captured men were marched at gunpoint back to Jasper.

“During the march back to town, the prisoners suffered verbal abuse from Morgan's men. Most of the prisoners said nothing. Forty-sever-year-old Joseph McDougal, a staunch Unionist schoolteacher, made some disparaging remarks to his captors.

“Because Morgan could not take the prisoners with him, he assigned Captian James W. Mitchell the task of paroling the home guard. Before paroling the men, Mitchell asked for directions to the Scioto River ford. No one volunteered the information.

“We do not know what happened next. Written accounts of the incident vary. We do know that McDougal was pulled from the group of prisoners and bound. (Another source: “Money was taken from the prisoner and Joseph only had ten cents. He stated that was ten cents more than he wanted them to have.”) He was asked to step out of line and was taken to another area and questioned. Captain Mitchell ordered him placed in a small boat (canoe) on either the Ohio & Erie Canal or the Scioto River. He then ordered two of his men to shoot McDougal, who was struck below the right eye and in the chest. (Another source: “The canoe drifted along down the river, with the bloody corpse of McDougal as a warning to those who planned to resist the raiders.”)

“We do not know what provoked the raiders to take this action. Very few civilians were killed during the raid, and then only if they fired on the raiders first.

“Joseph McDougal is buried behind the old Jasper Methodist

Church at the top of a hill. His broken tombstone inscription reads:

'

Joseph McDougal was shot by John Morgan's men July 16, 1863. Aged

47 yrs 7 ms 9 ds.'

“McDougal was survived by his wife, Elizabeth, and five children

ranging in age from one to seventeen years. Before leaving town the

raiders stole one of the widow's horses.

"A number of other Jasper residents had horses and valuable taken by the raiders.

“In 1863, Jasper was a bustling canal town of about 160 people. The town's stores served both canal traffic and local farmers.

“Angered by the citizens' resistance at the barricade, the raiders were violent in their looting and destruction. They burned all manner of buildings, barns, stables, and mills.

“They torched the Charles Miller sawmill and lumberyard, located between the canl and the river. They also burned Miller's canal boat. An attempt to burn his private bridge over the canal failed.

“After spending several hours in Jasper, the raiders crossed and burned the county bridge across the canal.

“Morgan's men turned left and rode approximately one-half mile upstream to the Scioto River ford.”

Morgan was eventually thwarted in his attempts to recross the Ohio River, and he was forced to surrender what remained of his command in northeastern Ohio near the Pennsylvania border.

Morgan and other senior officers were kept in the Ohio state penitentiary, but they tunneled their way out and casually took a train to Cincinnati, where they crossed the Ohio to safety. Morgan was killed less than a year later in Greeneville, Tennessee by a Union cavalryman after refusing to halt while attempting to escape.

Harriet Parrott, Daughter of Joseph McDougal Morgan's Grave

Sources:

Lora Schmidt Cahill and David L. Mowery. Morgan's Raid Across

Ohio: The Civil War Guidebook of the John Hunt Morgan Heritage Trail.

2014.

https://books.google.com/books?id=KkkPCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA115&lpg=PA115&dq=morgan%27s+raid+and+jasper+ohio&source=bl&ots=9R2zLtJr1l&sig=qpEz5UBBaa3juR7YQoloY5iEKbc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjakdvJjrPZAhUJ0FMKHZliABEQ6AEIYjAI#v=onepage&q=morgan's%20raid%20and%20jasper%20ohio&f=false

“Morgan's Raid into Ohio.” https://www.carnegie.lib.oh.us/morgan.

Phyllis

Kirkendall. “Jasper,

Ohio: Pictures and Information.” Pike County Messenger.

“Morgan's Raid In Indiana.”

https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/5817/5354