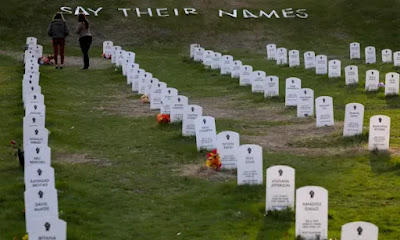

An art installation in Minneapolis, Minnesota, called Say Their Names honors people who were killed by police. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

A new study on fatal police violence shows more than half of killings by police were left unreported in the last 40 years, and that Black Americans were estimated to be 3.5 times more likely to die from police violence than white Americans.

Researchers estimate that the US National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), the government system that collates all death certificates in the USA, failed to accurately classify and report more than 17,000 deaths as being caused by police violence during the 40-year study period.

(GBD 2019 Police Violence US Subnational Collaborators. “Fatal police violence by race and state in the USA, 1980–2019: a network meta-regression.” The Lancet. Volume 398, ISSUE 10307, P1239-1255, October 02, 2021.)

The burden of fatal police violence is an urgent public health crisis in the USA. Mounting evidence shows that deaths at the hands of the police disproportionately impact people of certain races and ethnicities, pointing to systemic racism in policing.

Between 1980 and 2018, the age-standardised mortality rate due to police violence was highest in non-Hispanic Black people (0·69 [95% UI 0·67–0·71] per 100 000), followed by Hispanic people of any race (0·35 [0·34–0·36]), non-Hispanic White people (0·20 [0·19–0·20]), and non-Hispanic people of other races (0·15 [0·14– 0·16]).

This means more than half of all deaths due to police violence the study estimated in the USA from 1980 to 2018 were unreported in the National Vital Statistics System – a federal tracker of deaths in the United States – with three independent, non-government, open-source databases: Fatal Encounters, Mapping Police Violence and The Counted. Compounding this, researchers found substantial differences in the age-standardised mortality rate due to police violence over time and by racial and ethnic groups within the USA.

The study found that the NVSS underreported 55.5% of these deaths overall, but that percentage rose to 59.1% when reporting deaths among Black Americans.

The rate of police killings for non-Hispanic Black victims was about 3.5 times higher than that of non-Hispanic white people, and Hispanics were 1.8 times more likely to be killed by police violence than non-Hispanic white people.

The study confirms a pattern of systemic racism in policing, predominantly burdening communities of color, the study's co-author Eve Wool says.

"Even when unarmed, Black Americans experienced disproportionately high levels of police contact, even for crimes that Black and white folks committed at the same rates," Wool told ABC News.

(Kiara Alfonseca. “More than half of US killings by police go unreported: Study.” ABC News. September 30, 2021.)

Inaccurately reporting or misclassifying these deaths further obscures the larger issue of systemic racism that is embedded in many US institutions.

The paper found that men die from police violence at higher rates than women, with 30,600 police-involved deaths recorded among men and 1,420 among women between 1980 and 2019.

Researchers also noted the large conflict of interests inherent in tracking police-involved deaths. Coroners are often embedded within police departments and can be disincentivized from determining that deaths are caused by police violence. Yet, the same government responsible for this violence is also responsible for reporting on it.

Past studies have analyzed underreporting of fatal police incidents and how Black Americans disproportionately die from police violence, but previous research was conducted over much shorter time periods.

Understandings

Fatal police violence is a reality – “more than half of killings by police were left unreported in the last 40 years while Black Americans were estimated to be 3.5 times more likely to die from police violence than white Americans.” How are we to interpret these statistics as they apply to the causes of the discrepancies?

And, most importantly, how are we – responsible American citizens – going to stop the injustice?

An article written by Sendhil Mullainathan of The New York Times (2015) may illuminate the problems and offer solutions. Mullainathan is an American professor of Computation and Behavioral Science at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and the author of Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much. He concludes that we should absolutely eliminate police prejudice because it is wrong and because it undermines our democracy.

Yet, Mullainathan, like many others looks at the structural problems underpinning these killings, and he believes we are all responsible for those.

For example, consider that police bias means also accounting for the fact that African-Americans have a very large number of encounters with police officers. Every police encounter contains a risk.

Mullainathan posits that an officer might be poorly trained, might act with malice or simply make a mistake, and that civilians might do something that is perceived as a threat. Of course, the omnipresence of guns exaggerates all of these risks – risks that exist for people of any race. Having more encounters with police officers, even with officers entirely free of racial bias, can create a greater risk of a fatal shooting.

African-Americans have so many more encounters with police. Why? Of course, police prejudice may be playing a role. After all, police officers decide whom to stop or arrest. What else could play a part?

Mullainathan reports …

“Arrest data lets us measure this possibility. For the entire country, 28.9 percent of arrestees were African-American. This number is not very different from the 31.8 percent of police-shooting victims who were African-Americans. If police discrimination were a big factor in the actual killings, we would have expected a larger gap between the arrest rate and the police-killing rate.

“This, in turn, suggests that removing police racial bias will have little effect on the killing rate. Suppose each arrest creates an equal risk of shooting for both African-Americans and whites. In that case, with the current arrest rate, 28.9 percent of all those killed by police officers would still be African-American. This is only slightly smaller than the 31.8 percent of killings we actually see, and it is much greater than the 13.2 percent level of African-Americans in the overall population.”

(Sendhil Mullainathan. “Police Killings of Blacks: Here Is What the Data Say.” The New York Times. October 16, 2015.)

This seems too large a problem to pin on individual officers.

Mullainathan continues to explain …

“First, the police are at least in part guided by suspect descriptions. And the descriptions provided by victims already show a large racial gap: Nearly 30 percent of reported offenders were black. So if the police simply stopped suspects at a rate matching these descriptions, African-Americans would be encountering police at a rate close to both the arrest and the killing rates.

“Second, the choice of where to police is mostly not up to individual officers. And police officers tend to be most active in poor neighborhoods, and African-Americans disproportionately live in poverty.

“In fact, the deeper you look, the more it appears that the race problem revealed by the statistics reflects a larger problem: the structure of our society, our laws and policies.”

(Sendhil Mullainathan. “Police Killings of Blacks: Here Is What the Data Say.” The New York Times. October 16, 2015.)

Mullainathan believes the war on drugs illustrates this kind of racial bias. African-Americans are only slightly more likely to use drugs than whites. Yet, they are more than twice as likely to be arrested on drug-related charges. One reason is that drug sellers are being targeted more heavily than users. With fewer job options, low-income African-Americans have been disproportionately represented in the ranks of drug sellers.

In addition, the drug laws penalize crack cocaine – a drug more likely to be used by African-Americans – far more harshly than powder cocaine. Laws and policies need not explicitly discriminate to effectively discriminate.

And, of course, poverty plays an essential role in all of this. Jens Ludwig, an economist at the University of Chicago who also directs the Crime Lab there, points out: “Living in a high-poverty neighborhood increases risk of violent-crime involvement, and in the most poor neighborhoods of the country, fully four out of five residents are black or Hispanic.”

(Sendhil Mullainathan. “Police Killings of Blacks: Here Is What the Data Say.” The New York Times. October 16, 2015.)

Individual police officers did not set these economic policies that limited opportunities or create the harsh sentencing policies that turn minor crimes into lifetime sentences. We must understand the social institutions that intimately tie race and crime.

In her book, “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” Michelle Alexander argues that the American criminal justice system itself is an instrument of racial oppression. “Mass incarceration operates as a tightly networked system of laws, policies, customs and institutions that operate collectively to ensure the subordinate status of a group defined largely by race,” she says.

Let me repeat this important distinction: the structure of our society, our laws, and our policies contribute to fatal police violence and the disproportionate impact on people of certain races and ethnicities. There are structural problems underpinning these killings. We are all responsible for those. Why? Systematic racism is deeply rooted in our culture. That includes political and governmental agencies as well as social institutions.

Research by Michael Siegel published in the Boston University Law Review (2020)

concludes that individual-level interventions cannot adequately address racial disparities in fatal police violence and that confronting and remedying the consequences of a long history of racial residential segregation and structural racism is necessary.

Siegel reports that efforts to ameliorate the problem of fatal police violence “must move beyond the individual level and consider the interaction between law enforcement officers and the neighborhoods they police. Ultimately, countering structural racism itself, particularly in the form of racial segregation, is critical.”

The most immediate implication for city officials is that inherent-bias training offered to police officers should include not only training in how they deal with individuals on account of race but also training in how they deal with entire neighborhoods based on the racial makeup of those neighborhoods.

And, speaking of the environment, the entire relationship between police officers and the communities living in largely Black neighborhoods must be restructured.

Siegel's findings …

“Police officers must invest in the neighborhoods they police. They must begin to see these neighborhoods in an entirely different way. They must learn to see not only the segregation, not only the disadvantage, but also the humanity, the resilience, the love, the strength, the hope, and the promise.

“At an even deeper level, cities must ultimately confront the fact that they have segregated their Black population into neighborhoods with concentrated disadvantage. This can be remedied only by programs designed to racially integrate neighborhoods (where the community favors such an approach) and otherwise to pour resources into segregated neighborhoods to repair the damage that has resulted from racial inequities.”

(Michael Siegel. “Reacial Disparities In Fatal Police Shootings: An Empirical Analysis Informed By Critical Race Theory. Boston University Law Review, Vol. 100:1069. May 2020.)

To close, the Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America finds that structural racism – the normalized and legitimized range of policies, practices, and attitudes that routinely produce cumulative and chronic adverse outcomes for people of color, especially black people – is the main driver of racial inequality in America today.

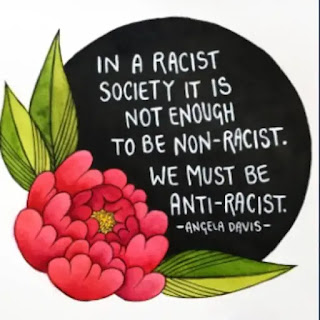

The first step in fixing a problem is acknowledging that a problem might exist. Because of white privilege, understanding structural racism is an effort that white scientists are not forced to make. We each must make a conscious decision to be anti-racist,

What does it mean to be anti-racist? Is it the same as “not racist”?

The National League of Cities deliniates the difference:

“'Not racist' often refers to a passive response to the generational trauma and pain inflicted on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in the United States. It does not require action – for example proactively challenging a system that has operated in this country since its “founding.”

“To be 'not racist' is to ignore 400 years of history that informs the root causes of inequities we see in all aspects of American life. These inequities in education, criminal justice, housing, healthcare, and all policy areas are the result of intentional and racist institutional policies, practices, and procedures. They exist on purpose.

“Because racism is the foundation upon which our society and institutions stand, choosing to interact with these institutions in a neutral way allows them to thrive. Racism can result from racist action and/or inaction, which results in complicity that creates or maintains racial inequities.

“Being 'not racist' does not require active resistance to and dismantling of the system of racism. Being 'anti-racist' does.

“Anti-racism is also a system – a system in which we create policies, practices, and procedures to promote racial equity. Anti-racism generates antiracist thoughts and ideas to justify the racial equity it creates by uplifting the innate humanity and individuality of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

“Anti-racism recognizes that there are no traits inherent within a racial group solely because of the color of their skin. Anti-racism forces us to analyze the role that institutions and systems play in the racial inequities we see, rather than assign the blame to entire racial groups and their 'behavioral differences' for those inequities.”

(Jordan Carter. “What Does It Mean to Be an Anti-racist?” National League of Cities. July 21, 2020.)

Speaking from a psychological viewpoint, here is the challenge for all of us:

“Although interpersonal or personally mediated racism stands in contrast to structural racism, individuals have responsibility for perpetuating or changing the systems which contribute to it. A component of privilege is the luxury of not examining the social systems that contribute to privilege, and therefore, many white people and others with whiteness privilege are unaware of how structural racism selectively contributes to their success.

“Awareness of systemic racism makes it possible for us to address the structures and practices that enforce inequities within the biological and medical sciences.”

(Sonnet S. Jonker, Cirila Estela Vasquez Guzman, and Belinda H. McCully. “Addressing structural racism within institutional bodies regulating research.” Journal of Applied Psychology. June 02, 2021.)

“In its majestic equality, the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread.”

– Anatole France (1844-1924) French poet, journalist, and novelist

No comments:

Post a Comment