“Eliza was fleeing her captors with her young son in her arms when she was stopped short by the banks of the frigid Ohio River. With the unthinking courage that comes from desperation, she leapt from one ice floe to another, occasionally falling into the freezing water and hoisting herself up, until arriving on the riverbank across the state line.

“After witnessing her harrowing journey, a white man who should have captured her ended up helping her ashore instead, directing her to a safe house rather than into the arms of her pursuers.

“The story of a white man moved to save a slave so tugged at the heartstrings that the abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe included a version of it in her novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” For many who were assigned the book to read in school, the tale of Eliza is their first indelible image of escape from slavery.

“The actual flight of Eliza began in Kentucky and ended on the riverbanks in Ripley, Ohio, abolitionists at the time said, making a white character based on a patroller one of the best-known saviors. But the true Moses of Ripley was a former slave named John P. Parker, who helped make the town a major nexus in the path of kidnapped Africans and their descendants determined that their lot in life was not to be thought of as property.”

(Monica Drake. “In Ohio, a Warrior Against Slavery.” The New York Times. February 24, 2017.)

Abraham Lincoln allegedly called Harriet Beecher Stowe "the little lady who started the big war" after she wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin in 1852. It became an instant best seller The book was included on The Library of Congress' list of books that shaped America and has been called the most influential novel ever written by an American.

History Note:

Uncle Tom's Cabin sold 15,000 copies within the first month, 50,000 through May, and 100,000 by the end of June. A total of 310,000 copies were purchased in the United States and more than one million in Great Britain during the first year. Millions of people heard the book read aloud or borrowed copies to read themselves. Stowe went on a speaking tour in Great Britain in 1853 and raised money for the antislavery cause

Uncle Tom’s Cabin narrates life on a southern plantation, portraying African American characters who are strong, faithful, and virtuous. They are victimized by a brutal system of violent whippings and the sexual exploitation of enslaved women. The enslaved men and women want to enjoy their liberty as humans and come close to violent rebellion to win it.

Masters, overseers, and slave catchers in the story are corrupted by slavery and drink, rather than being directly demonized, because Stowe wanted to appeal to southerners to change their minds about slavery. In Stowe's view, no one was corrupt by nature; the system of slavery spoiled everything and everyone it touched.

Examine that view today. Stowe's fictional account of slavery is open for criticism for its watered-down treatment of the horrible bondage. Though grounded in personal experience – as a young woman, the Ohio native visited a plantation in Kentucky which would serve as inspiration for the Shelby Plantation – the book is obviously overly sentimental towards subjugation.

Reading the book, we quickly understand Stowe did not have the same insight or understanding as an enslaved person experiencing those horrid conditions. Her reliance on racial stereotypes exposes her misconceptions about black people, discrediting her authority even more. While she maintains an honesty of theme, her portrayal must be judged by the reality of the times. Give her credit for pushing against dominant cultural beliefs of the time. It is impossible to read Stowe’s book and not come away with a seething hatred of the entire institution of slavery.

The truth. What is more noble than the pursuit of truth? History demands that we study the past to improve the future. As we do so, we Americans must find solid evidence in order to help evoke needed change. To be guilty of shielding students from the ugly history of slavery not only contributes to their ignorance but also distortd the process and the product of historical inquiry.

Teaching The Truth

Teaching Critical Race Theory is a subject of controversy all over America. CRT has shot to the forefront of public discourse in the U.S., appearing in countless headlines and sparking intense debates across the country about its significance and use. The core idea is that race is a social construct, and that racism is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies. Supporters say CRT teaches how racism has shaped public policy and life in America.

The theory says that racism is part of everyday life, so people – white or nonwhite – who don’t intend to be racist can nevertheless make choices that fuel racism.

Some critics claim that the theory advocates discriminating against white people in order to achieve equity. They mainly aim those accusations at theorists who advocate for policies that explicitly take race into account. (The writer Ibram X. Kendi, whose recent popular book How to Be An Antiracist suggests that discrimination that creates equity can be considered anti-racist, is often cited in this context.)

Critics Of CRT In Ohio

Here, in Ohio, a growing group of Ohio's Republican lawmakers, despite good evidence to the contrary, say they're troubled by CRT and the way some schools are teaching history. They want to put a stop to it.

Opponents to the theory, like the sponsors of House Bill 322, call it a dangerous and divisive theory.

If passed, HB 322 would prohibit schools from requiring teachers to use examples from current events or ongoing controversial issues in their classrooms. And schools couldn't require lessons about current pieces of legislation or the groups lobbying for and against them.

What is at the heart of HB 322? The proposed legislation centers around how racism would be taught. Teachers couldn't be required to "affirm a belief in the systemic nature of racism, or like ideas, or in the multiplicity or fluidity of gender identities, or like ideas."

"It is designed to look at everything from a ‘race first’ lens, which is the very definition of racism," Rep. Don Jones, R-Freeport, said in a statement announcing the bill. "CRT claiming to fight racism is laughable. Students should not be asked to ‘examine their whiteness’ or ‘check their privilege.' This anti-American doctrine has no place in Ohio’s schools."

(Anna Staver. “House Republicans introduce bill to ban teaching of critical race theory in Ohio.” The Columbus Dispatch. September 22, 2021.)

Attempts To Whitewash Racial History In Ohio

Laws forbidding any teacher or lesson from mentioning race/racism, and even gender/sexism, would put a chilling effect on what educators are willing to discuss in the classroom and provide cover for those who are not comfortable hearing or telling the truth about the history and state of race relations in the United States.

Those who support bills against telling the truth about the history of racism, gender, and sexism and their continued existence accuse instructors of teaching revisionist history and seeking to tamper with vaulted nationalistic views of our national origins. They are attempting to forbid essential inquiry and interpretation.

However, the truth is that teachers are not attempting to “revise” anything about the history of our country and our state; instead, they are providing a true picture of the past in order that students may learn from these events. Part of that instruction is exposing inaccuracies and providing better research to understand relevance to today. Race and sex remain powerful determinants in America – even when laws prohibit race or sex discrimination. Attempting to whitewash the truth is painfully suspect of ulterior motives – justifications for censorship at profound odds with our free speech tradition.

Ohio History

Today, I want to offer some truths about Ohio and conditions concerning race and slavery since our European settlement. Nothing can undercut the immense, positive role the state has played in the history of abolition and civil rights. In fact, in my view, understanding “the way it was” only increases respect for those fearless people who worked so hard (and continue to work) to establish freedom and justice for all people in the Buckeye State.

Ohio And the Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 prohibited slavery in the territory, thereby making the Ohio River a natural dividing line between the free and slave states of the country. Did you know that unanimous consent from the states was required for the Northwest Ordinance to be passed?

So, you may ask why the Southern states agreed to the provision. Pro-slavery Southerners were willing to go along with this because they hoped that the new states would be populated by white settlers from the South. They believed that although these Southerners would have no enslaved workers of their own, they would not join the growing abolition movement of the North.

(Editors. “Congress enacts the Northwest Ordinance.” History. July 12, 2021.)

Under the Articles of Confederation, the power of the national government to potentially curtail slavery in the southern states was almost nonexistent. With slavery being established in Kentucky and Tennessee, it was also obvious that the remainder of the South would be allowed to adopt that practice without issue.

Another reason for southern acceptance – the primary crop of most plantations at that time was tobacco – a crop that could only be grown profitably with the assistance of slave labor. And, by outlawing slave labor in the Midwest, the southern planters protected themselves from economic competition.

(Dan Bryan. “The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and its Effects.” www.americanhistoryusa.com. April 8 2012.)

Article 6 in the Ordinance of 1787 simultaneously banned and enforced slavery, a fact that still intrigues, though baffles, students of American history. It is a lesson in ambiguity.

Article 6 strengthened slavery with an immigration law that prevented the Northwest Territory from giving refuge to a slave. It authorized a slaveholder to capture a runaway who made it safely to the Old Northwest. Consequently, the Ordinance of 1787 offered the United States its first free zone, its first restriction on black immigration, and its first national labor law. This anomaly made it possible for slavery to continue in various forms in the Illinois country long after adoption of the Ordinance of 1787.

“There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted: Provided, always, that any person escaping into the same, from whom labor or service is lawfully claimed in any one of the original States, such fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labor or service as aforesaid.”

Article 6, Northwest Ordinance of 1787

History Note:

The Northwest Ordinance showed the influence of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson always maintained that the decision to emancipate slaves would have to be part of a democratic process; abolition would be stymied until slaveowners consented to free their human property together in a large-scale act of emancipation.

“There have been different opinions as to the comparative merit of the prohibition of slavery originally reported in the Ordinance of 1784 and the article of compact actually passed in the Ordinance of 1787. The former, which was introduced by Jefferson, included all the Western Territory of the United States and because of this fact was apparently a greater limitation of slavery. It postponed, however, the prohibition until the year 1801.

“The prohibition in the Ordinance of 1787 became immediately effective. If it had not gone into effect until the year 1801 slavery would probably have been established in all sections of the Northwest Territory and it would have been very difficult to exclude it.

“Different writers have declared that it would not have been excluded at all and that Ohio would have entered the Union as a slave state. This is a matter of opinion, however.

“Others have declared Jefferson's prohibitory provision would have been much more effective, as it included all the western territory from the lakes to the gulf. This, of course, must also remain a matter of opinion.”

In view, however, of the controversy over the question of slavery when Illinois and Indiana were admitted into the Union even with the prohibition of slavery in the Ordinance of 1787, it is extremely doubtful whether states formed out of the entire Western Territory if slavery had been permitted therein to the year 1801, would have consented to its exclusion after that date; and if they had not consented the action of Congress would have been at least very problematic.”

(C.B. Galbreath.Thomas Jefferson's Views On Slavery. Ohio History Journal. 1925.)

Ohio Statehood

When Ohio, Indiana and Illinois were carved out of the Northwest Territory, each state debated whether to legalize slavery. It was the Northwest Ordinance that paved the way for Ohio to become the seventeenth state of the United States.

The Ohio Constitution of 1803 prohibited slavery, honoring one of the provisions of the Northwest Ordinance. The convention members failed to extend the suffrage to African-American men in the constitution by a single vote. The convention approved the Constitution on November 29, 1802, and adjourned.

One must note the contributions of Ephraim Cutler, political leader and jurist. An attempt to add limited slavery to the proposed constitution of Ohio in 1802 was defeated after a major effort led by Cutler, who represented Marietta, the town founded by the Ohio Company. His anti-slavery contribution to was made by introducing the section to the Ohio Constitution that excluded slavery from the State and casting the deciding vote for Ohio to enter the Union as a Non-Slave State.

Washington county, Ohio had a small but growing population of anti-slavery advocates. With his extensive contacts with Quakers and other anti-slavery advocates throughout Ohio, Judge Cutler began to organize people willing to assist fugitive slaves. It should be noted here, that while the first two events of 1793 relative to slavery had worked against the anti-slavery principle, one very positive event favorable to anti-slavery also had occurred in 1793.

(The Upper Providence of Canada (Ontario) had passed legislation to emancipate their slaves and had banned all forms of slavery. This meant that fugitive slaves from the United States could cross the international border into Canada, and avoid recapture under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793. Thus Canada became the safe haven for fugitive slaves from the Southern states, especially those close enough to the Ohio River.)

(Henry Robert Burke. “Judge Ephriam Cutler and Constitution.” Window To the Past. 1998.)

Stephen Middleton, professor of constitutional history at North Carolina State University says this of the views on slavery in Ohio…

“There were many like Thomas Jefferson who favored slave-owning and vehemently opposed giving blacks political rights. Indeed, the vast majority of white emigrants in Ohio opposed equality between the races …

“... leaders of the time like William Henry Harrison – governor of the territory and future president of the United States – argued that Virginia law protected slave owners and these law secured their property interest in slaves; they also wanted to exclude blacks from the political culture of the new state …

“Nathaniel Massie (famed surveyor commonly known as the “founder of Portsmouth”) had owned slaves in Virginia and Kentucky. He would have carried them to Ohio had it not been for the prohibition in Article VI. Massie admitted the economic benefits of owning slaves, yet he too recognized how slavery might ultimately harm the economy of Ohio. Although slavery might temporarily contribute to our property, he vowed to vote against it.

“Abolition was not a major issue for any political party in 1800, and few whites could have predicted that race or slavery would become controversial in Ohio.”

(Stephen Middleton. The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio. 2005.)

The purpose of the state, the Ohio constitution of 1802 declared, was “to establish justice, promote the welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” The theory of natural rights formed the underpinnings of both federal and state governments, including that of Ohio.

One of the challenges facing Americans and Ohioans, therefore, was reconciling the ideals of the republic with the history of American slavery and legalized discrimination.

Ohio was the fastest-growing state in antebellum America and the destination of whites from the North and the South. This helped make it a legal battleground for two camps – one that favored the use of state power to further racial discrimination, and the other to advance equality under the law for all Americans.

History Note:

“The Ohio Constitution included an indentured servant provision, which authorized residents to hold blacks as servants until they were 21, if male, and 18, if female. These servants could be held for longer periods providing “if they enter into indenture while in a state of perfect freedom.” Moreover such servants could be licensed to work outside of Ohio for up to one year and for longer periods under apprenticeships. Under the indentured servants and apprenticeship practices, whites could legally gain authority over black children for many years.

(Steven Middleton. The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio www.ohioswallow.com. 2005.)

After Statehood

So, the passage of the Ohio Constitution did not mean that free black Ohioans were complete citizens. The political battles were fierce and, although pro-slavery efforts failed, the new state quickly approved laws that imposed punitive restrictions on the freedom of African Americans. Beginning in 1803, the Ohio legislature enacted what came to be known as the Black Laws.

Whatever the individual states decided, the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 made it legally obvious that no slave became free simply by entering a free state. From almost the time Ohio was settled, the state became the hunting ground for slave catchers who earned rich rewards for returning runaway slaves to their Southern masters.

Ohio had prohibited slavery, but only in the sense that no one could buy or sell slaves within the state.

The Black Laws were created with one specific objective: to make life for African Americans in Ohio so intolerable that these men and women would not use the free state as a refuge from the oppression of slavery.

The Black Laws included a registration law that required blacks entering the state to show on demand a certificate of freedom, authenticated by a court of record and filed with the clerk in the county where they resided. The residency law directed African Americans already living in the state to register with a county clerk. A labor law provided that Ohio residents could hire only those African Americans possessing a certificate.

The state fugitive slave

law granted slave owners a right of recapture and penalized anyone

who interfered with the process. Revised in 1807, the registration

law provided that, within twenty days of their entry into Ohio,

African Americans were required to enter into a five-hundred-dollar

bond with two property holders and that these free-

holders, if

called upon, would be required to apply the funds to the welfare or

liability of the emigrant.

Other Black Laws barred African Americans from enrolling in the militia, serving on juries, and attending public schools.

History Note:

“As black population swelled during the 1930s, Ohio whites became increasingly worried about the possible social integrations of blacks and whites. The Black Laws fostered segregation in Ohio, even though the state did not officially use the term. Former southerners controlled much of the legislature and newspapers. Ohio officials charged slave owners with holding Ohio as a dumping ground for diseased and disabled blacks who were no longer productive.”

(Steven Middleton. The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio www.ohioswallow.com. 2005.)

The 1840s – Changes Finally Occur

By the 1840s, progressive whites in the North and blacks had become optimistic, believing that they had finally begun to change hearts and minds.

There is evidence that Ohio judges began to place greater emphasis on fairness in their courtrooms and that they began to minimize the effects of the Black Laws whenever possible.

Not until 1841 did Ohio enact a law so that any slave brought into the state automatically became free. Before then, Southern slave owners regularly visited Ohio and especially Cincinnati accompanied by slaves. Ohio laws allowed slave owners to bring their slaves into the state for unspecified periods of time before those slaves were considered free. Slaves who gained freedom soon discovered that there was “freedom” and there was “freedom”:

(Greg Hand. “Ohio Was Not Home-Free For Runaway Slaves.” Cincinnati Magazine. February 18, 2016.)

“That no black or mulatto person or persons shall hereafter be permitted to be sworn or give evidence in any court of record, or elsewhere, in this state, in any cause depending, or matter of controversy, where either party to the same is a white person.”

5

Laws of Ohio 53, Section 4, approved January 25, 1807

One Case and Its Relevance

In 1841, the Colored American, an African American newspaper, ran a story entitled “Civil Condition of the Colored People in Ohio.” It reported the murder in Cincinnati of a black man by a white.

The Colored American had frequently published articles describing how the Black Laws had subordinated and degraded African Americans. It reported this story not only because it was news that merited cover age but, more important, because it illustrated the continued injustice of the Black Laws.

This article specifically exposed how the “oath law” protected unscrupulous whites by excluding “the testimony of a colored person against a white person.” In previous articles, the paper had reported numerous instances of whites embezzling, swindling, and even stealing property and money from blacks. The paper had already predicted that the testimony law would enable “a white to murder a colored man, in the presence of colored persons only, and under the operations of this law, or as it had been interpreted, the murderer might go unpunished.”

The 1841 case tragically proved the accuracy of this prediction

The “Negro evidence law” was only one of many statutes Ohio lawmakers enacted to accomplish this purpose.

The episode involved Charles Scott and his brother (whose name is unknown), two free African Americans who lived in Cincinnati. White men hired the Scotts, ostensibly to help them drive cattle across the Ohio River into Kentucky. The editors of the Colored American suspected that whites, including local constables in Covington, had invented the scheme to kidnap the men.

Once in Kentucky they

immediately had the brothers arrested as fugitive slaves. Luckily, a

white individual from Cincinnati immediately came forward to offer

testimony of the free status of Charles’s brother. Charles,

however, remained in jail for six weeks, until

another Cincinnati

white finally vouched for him.

Infuriated by his ordeal, Charles Scott immediately filed a complaint against his abductors in Hamilton County. The kidnappers demanded that he withdraw the suit, and when Charles refused, they shot him dead “in his own house, by his own fireside.”

The Hamilton County prosecutor obtained a warrant for the arrest of the assailants. When they were brought to trial, the testimony law became the center of the controversy.

Under this 1807 law, “no black or mulatto person” was “permitted to be sworn or give evidence in any court” in Ohio “where either party” was “a white person.” The testimony law barred Scott’s wife, a witness to the murder, from offering evidence against the white defendants. The prosecution called another witness, a light-complexioned mulatto woman, whose testimony was challenged on grounds that the rules of evidence also applied to this class of persons.

Forced to consider these

objections, the trial judge faced a disturbing dilemma: should he

strictly adhere to the law and allow the accused to go free, since

there were no approved witnesses against the defendants? Or should he

admit the mulatto wit -

ness under a broad interpretation of the

statute? The judge chose the latter route, and the defendants were

convicted for the murder of Charles Scott.(The Colored American

did not report on their sentences, nor is the official transcript

of the trial available.

If strictly interpreted and enforced in the Charles Scott case, state law in 1841 would have protected the white defendants because neither a black nor a mulatto could have given sworn testimony against them. The murderers would have been set free.

(Steven Middleton. The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio www.ohioswallow.com. 2005.)

Since at least the early 1830s, the Ohio Supreme Court consistently had ruled that only persons with over 50 percent white blood were entitled to the privileges of whites. The judge in the Scott case made whiteness and blackness a variable and more subjective factor than the Supreme Court had established. Applying case law loosely, he concluded that various shades of persons could be at least 50 percent white.

While the Colored American

lamented the testimony law, it considered the Scott case a

hopeful

sign—a positive indication of a new day when “[t]he ‘Black

Laws’ will soon give way to make room for just ones.” The

correspondent looked to the day when common defense, safety, and

justice would become the norm in Ohio “without regard to

complexion.”

The murder of Charles Scott highlights the grave injustice of the Black Laws of Ohio. The subsequent trial also illustrates that Ohio judges were forced to take a stand on how these laws would be executed. However, we cannot be sure that the judge in the Scott case was defending black rights. He may have been acting to prevent violence that could go beyond the black community and threaten whites.

The editors of the Colored American considered the decision an important one. They used the Scott case to argue that a growing number of progressive whites had begun to realize that the testimony law under mined the prosecution of justice: “The Ohio people are beginning to arrive where they might necessarily expect to be carried by warring against right, as they have done in the enactment of such laws.”

Repeal of Black Laws … With Exceptions

On arriving in southern towns and hamlets, black Ohioans immediately began building institutions and working to educate their children. The state’s first independent Black church was founded in Cincinnati in 1815; by 1833, the state was home to more than 20 AME churches with a total membership of around 700 people. In 1834, African Americans in Chillicothe formed the Chillicothe Colored Anti-Slavery Society and announced it in a local newspaper.

In 1837, more than three decades after statehood, African Americans mobilized to petition the general assembly to repeal the black laws and support schools for their children. The movement began in Cleveland.

The Cleveland Journal commented that the petitions had been “received more favorably than was anticipated,” and the editors of The Colored American in New York reprinted the Journal’s story and praised black Ohioans for their “moral and intellectual strength.”

At the 1837 Ohio convention, fighting the black laws was an important agenda item. Delegates created a constitution for a “school fund institution of the colored people” designed to receive funds from private donors and, they hoped, from the state government. They also resolved to continue petitioning for repeal of the state’s black laws. To facilitate action, the convention published two forms that could be cut out of the newspaper and pasted onto larger pages that black Ohioans could sign.

Spring of 1838 was a thrilling moment for the black and white Ohioans who sought repeal of the state’s racist laws, but the fight was a long one. Eleven years later, in winter 1849, the state legislature finally repealed most of the Black Laws – the result of years of pressure and lobbying, as well as instability in the two-party system that had defined state and national politics since the 1830s.

Even then, however, the state constitution’s mandate that only white men could vote remained; it would not be nullified until the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1870.

(Kate Masur. Until Justice Be Done: America's First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction. 2021.

Shortly after the repeal of the first Ohio Black Laws though, more "black laws" were added. The anti-miscegenation law passed in 1861 aided in defining Ohio as a state that was capable of opposing slavery while still upholding the racialized caste system present throughout the country during the nineteenth century.

While it is true that Ohio was not alone in its efforts to pass legislation that would prohibit marital and sexual relationships between black and white couples during the mid-nineteenth century, anti-miscegenation legislation showed how a state could condemn the institution of slavery but remain racist.

Ohio’s legislature passed the state’s anti-miscegenation law on January 31, 1861. The final statute included prohibitions of both sex and marriage between “any person of pure white blood...[and] any negro, or person having a distinct and visible admixture of African blood” and penalties for both the principals parties to and officiants of interracial marriages.\

In 1861 even Ohio Republicans could “agree on slavery but not on racial issues.” And second, Republicans from southern Ohio were concerned with appearing conciliatory without abandoning party lines in order to avoid further agitating the neighboring slave states of Kentucky and Virginia, thus seeking to preserve the economic ties that existed between southern Ohio and the border states.

Sarah McCrea explains …

“'Integration anxiety' was especially prolific in the state of Ohio in the period just before and during the Civil War. The looming threat of the spread of slavery to the North just before the conflict, as well as of emancipation throughout, ushered in a bevy of speculation surrounding what would happen if the black population of Ohio were permitted to increase unchecked.

“One major conclusion that several Ohio legislators drew was that an increase in the black population would, in turn, cause an increase in marital and sexual relationships between the white and black communities.

“(i.e.) Ohio senators Richard A. Harrison and Thomas J. Orr argued that both Ohio and the United States were intended by God to be the domain of the white man79 and both believed that a law to prohibit interracial sex and marriage was necessary in the crusade to '(keep) Ohio for white men.'

“Another way in which an

increased number of intimate interracial relationships (marriages,

specifically, in this case) put Ohio’s racialized social hierarchy

in jeopardy was in legitimizing not only the off-spring of such

relationships, but also the couples’ relationships. In both cases,

unregulated interracial marriage would allow white men to leave

property and wealth to their black and mixed-race spouses and

children upon death

and black men to control the inheritance of

their white wives upon marriage.”

(Sarah McCrea. “In Black and White: The Sociopolitical Rhetoric Surrounding Anti-Miscegenation Attitudes in Ohio.” Senior Independent Study Theses. College of Wooster Libraries. 2016.)

These attempts would play out at the national level during the presidential election of 1864, and the end of the Civil War would usher in a new surge of anti-miscegenation attitudes in Ohio during the Reconstruction period.

However, this later wave of opposition to interracial sex and marriage would appear primarily in the public forum of the press as opposed to the fairly closed discussions of the Ohio legislature. The press’s involvement during the Reconstruction period would bring ordinary, and mostly white, Ohioans into the mix as the intended audience for discussions of “racial mixture” and its perceived effects on white Ohio.

As a result, public figures began to increase their use of common institutions such as Christian belief and white male paternalism toward white women to justify their anti-miscegenation attitudes and to encourage their development within the general public.

(Sarah McCrea. “In Black and White: The Sociopolitical Rhetoric Surrounding Anti-Miscegenation Attitudes in Ohio.” Senior Independent Study Theses. College of Wooster Libraries. 2016.)

Reconstruction

Ohioans only reluctantly accepted the Fourteenth and the Fifteenth Amendments after denying full civil and political rights to African-American several times in the past. The enabling legislation that was included as part of these amendments allowed Congress to expand the jurisdiction of the federal courts and remove some cases from local juries and transfer them to the federal court system.

Wade Minahan writes: “It is evident that Ohio had a

more profound effect on Reconstruction than Reconstruction had on

Ohio. Ohio’s military leaders won the war and administered

Congressional Reconstruction of the Southern States.” Its political

leaders took advantage of a temporary Republican super majority to

enact these two Amendments whose effect was small at the time, but

became much more profound in the next century. Finally, Ohio’s

Presidents and future Presidents helped lead the Nation from a time

of schism and War into the 20th Century.

(Wade Thomas Minahan. “A New Birth of Freedom: The Effect of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Ohio Law.” University of Nevada, Reno . August, 2015.)

Unfortunately, Reconstruction had not provided one crucial freedom right that may have made a backlash easier to conquer: the access to land. Freed slaves in the South could not make a living without access to the 40 acres and a mule they had been promised. This meant a life of share cropping, where former masters were able to trap former slaves in complicated agreements that left white men in control of black labor yet again.

Post-Reconstruction

Most historians mark the end of Reconstruction in 1877, as a result of the election of Ohioan Rutherford B. Hayes to the presidency in 1876. After a dispute in vote counts, Democrats and Republicans ended the election in the “Compromise of 1877.”

Democrats allowed Republicans to take the presidency, if they promised to remove the federal troops in the South that protected black citizens from racial terrorism. The deal was made, and Reconstruction began to come to an end.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Southern whites took control of the historic narrative of slavery and the South, building a Lost Cause ideology that still permeates American life. In this view, the Civil War is about state’s rights and preserving a southern way of life. In addition slavery is considered a “peculiar institution” that was benevolent to black men and women who could not live on their own. Instances of racial violence grew, Confederate memorials began to pop up, and black names were removed from the legislature and voter rolls.

“A historical study of Columbus development, found covenants prolific in theearly 20th century, particularly between 1921 and 1935 where 67 of 101 (or 67% of all) subdivisions platted in the developed during this time to included restrictive convents.”

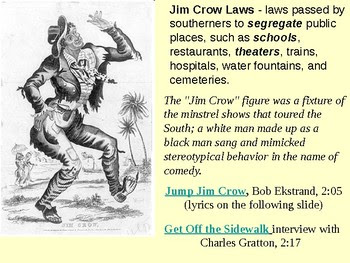

Jim Crow Laws were not present in Ohio and most of the North, because there was not yet a large black population. Most black Americans lived in the South, because that is where they or their ancestors had been brought to work as slaves. This would not change until the Great Migration (1916-1970). The North was still segregated, but with fewer laws on the books.

(Kieran Robertson. “The Long Struggle for Freedom Rights.” Ohio History Connection. June 02, 2020.)

“By 1914 the NAACP of Cleveland noted that 'a noticeable tendency toward inserting clauses in real estate deeds restricting the transfer of the property to colored people, Jews, and foreigners generally.'”

And still, social inequalities prevalent in the South could also be found in the North. Although the Ohio Accommodations Law of 1884 banned discrimination on the basis of race, segregation was still practiced in Ohio through the 1950s at skating rinks, pools, hotels, and restaurants. The Ohio Civil Rights Commission found wanton disregard of the laws against discrimination.

Ohio sought to remove such segregations by creating the Ohio Civil Rights Commission in 1959. Its purpose was to monitor and enforce the law preventing discrimination in employment.

“Segregation never comes about because it ‘just is,’ as the term ‘de facto’ might also suggest. The bottom line is this: segregation has always involved some form of institutionally organized human intentionality, just as those institutions have always depended on more broadly held beliefs, ideas, and customs to sustain their power.”

– Carl H. Nightingale, Segregation - A Global History of Divided Cities

African Americans continued to receive unequal and often unfair treatment. By 1950, blacks represented six percent of Ohio's population. In 1954, the U. S. Supreme Court, in the case of Brown vs. the Board of Education in Topeka, ruled "separate but equal" facilities unconstitutional. Following this landmark decision, African Americans began to enter all-white schools and brought the segregation issue into the public eye.

With a 21st century perspective, teachers must approach the history of slavery, racial oppression, and sexual discrimination with messages that deliver the truth. Those who oppose critical race theory cannot effectively be the judges of their own prejudices unless they digest and assimilate the facts. We've come a long way since Stowe penned her famous novel exposing the hideous roots of human subjugation. Now, its time to put the novel in its proper context and realize that some 170 years later systematic racism still denies minority Americans freedom and justice.

Why teach the truth at the risk of rending a sacred fabric of white heritage of the country? Precisely because it is necessary to evoke change and establish greater vision before old forces rip the nation in two. We cannot continue to repress and distort facts just to feed a more pleasant, fictional version of American history.

To solve the problems of today, we must understand how

we got here. Let's face it: most people do not understand

institutional racism and structural racism … they don't even know

the history of prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism in their own

state. Why not? Many view these things as nonexistent in modern

society and government. At the risk of demeaning these nonbelievers,

I am convinced their ignorance rests largely on their own personal

prejudices, untruths, and distortions.

We

must employ the transformational power of deeply understanding our

history to realize our shared “blessings of liberty.” That

includes teaching our children to analyze, evaluate, and … yes,

even create new understandings toward a future of intelligent design

… and in constant search of the truth.

Remember

By Langston Hughes

Remember

The days of bondage—

And remembering—

Do not stand still.

Go to the highest hill

And look down upon the town

Where you are yet a slave.

Look down upon any town in Carolina

Or any town in Maine, for that matter,

Or Africa, your homeland—

And you will see what I mean for you to see—

The white hand:

The thieving hand.

The white face:

The lying face.

The white power:

The unscrupulous power

That makes of you

The hungry wretched thing you are today.

Langston Hughes, "Remember" from (New Haven: Beinecke Library, Yale University ) Source: Poetry (January 2009)

No comments:

Post a Comment