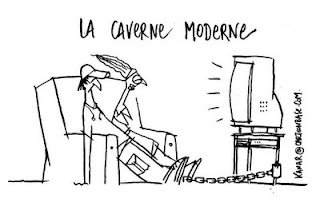

Plato, in "Book Seven" of the Republic, presents the Allegory of the Cave. The two elements of the Allegory of the Cave are the fictional metaphor of the prisoners and the philosophical tenets which the story is supposed to represent. The passage itself is not written from the perspective of the prisoners, but rather it is written as a conversation occurring between Socrates and Plato’s brother Glaucon. The allegory isn’t the story, but rather the fictional dialogues between Glaucon and Socrates.

Socrates asks Glaucon to imagine a cave in which prisoners are chained and held immobile: they are bound to the floor and unable to turn their heads to see what goes on behind them. They have been in this state of captivity since childhood. Not only are their arms and legs held in place, but their heads are also fixed, so they are compelled to do nothing but to gaze at a wall in front of them.

To the back of the prisoners, under the protection of the parapet, lie puppeteers who cast shadows on the wall. The prisoners vividly see the shadows, and they intently watch these forms cast by the men, completely unaware that they are shadows. There are also echoes off the wall from the noise produced from a walkway. The prisoners spend their lives interpreting these images because that is all they can see.

As Socrates is describing the cave and the situation of the prisoners, he conveys the point that the prisoners would be inherently mistaken as to what is reality. He explains that the puppeteers behind them are using wooden and iron objects to liken the shadows to reality-based items and people. The prisoners (unable to turn their heads) would know nothing else but the shadows, and they would perceive this as their own reality. In fact, the whole of their society would depend on their understanding of the shadows on the wall.

Plato explains that this part of the allegory shows what people perceive as real from birth is completely false based on their imperfect interpretations of reality and Goodness. The point of the allegory thus far is that the general terms of language are not "names" of the physical objects that someone can see. They are actually names of things that are not visible to most, things that people can only grasp with the mind. This line of thinking is said to be described as “imagination,” by Plato.

Next, Socrates asks Glacoun to suppose that a prisoner is freed and permitted to stand up. Socrates questions, if someone were to show this man the things that had cast the shadows, how would the prisoner be able to recognize them? He would believe the shadows he is accustomed to seeing on the wall to be more real than what he is shown. "And you may further imagine that his instructor is pointing to the objects as they pass and requiring him to name them, -will he not be perplexed? Will he not fancy that the shadows which he formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him?" asks Socrates.

Socrates prods Glacoun to perceive further that the man was compelled to look at the fire. Socrates continues, "Wouldn't he be struck blind and try to turn his gaze back toward the shadows, as toward what he can see clearly and hold to be real?"

And Socrates continues, "What if someone forcibly dragged such a man upward, out of the cave: wouldn't the man be angry at the one doing this to him? And if someone dragged the man all the way out into the sunlight, wouldn't he be distressed and unable to see even one of the things now said to be true?" (516a) The natural reaction of the prisoner would be to recognize only shadows and reflections.

Plato describes the vision of the real truth to be “aching” to the eyes of the prisoner, and how he would naturally be inclined to go back and view what he has always seen as a pleasant and painless acceptance of truth. This stage of thinking is noted as “belief.” The comfort of the aforementioned perceived, and the fear of the unrecognized outside world would result in the prisoner being forced to climb the steep ascent of the cave and step outside into the bright sun.

After some time on the surface, however, Socrates suggests that the freed prisoner would acclimate. He would see more and more things around him, until he could look upon the sun. He would understand that the sun is the "Form of the Good, the source of the seasons and the years, and is the steward of all things in the visible place, and is in a certain way the cause of all those things he and his companions had been seeing." After his eyes adjusted to the sunlight, he would begin to see items and people in their own existence, outside of any medium. (516b–c)

Plato recognizes this concept as the cognitive stage of thought. This point in the passage marks the climax, as the prisoner, who not long ago was blind to "The Form of the Good” (as well as the basic forms in general), is now is aware of reality and truth. When this enlightenment occurs, the man achieves the ultimate stage of thought, known as “understanding.”

Socrates next asks Glaucon to consider the new condition of this man:

1. "Wouldn't he remember his first home, what passed for wisdom there, and his fellow prisoners, and consider himself happy and them pitiable?

2. "And wouldn't he disdain whatever honors, praises, and prizes were awarded there to the ones who guessed best which shadows followed which?

3. "Moreover, were he to return there, wouldn't he be rather bad at their game, no longer being accustomed to the darkness?

4. "Wouldn't it be said of him that he went up and came back with his eyes corrupted, and that it's not even worth trying to go up?

5. "And if they were somehow able to get their hands on and kill the man who attempts to release and lead up, wouldn't they kill him?" (517a)

And, the ultimate question becomes: What if the man did return to the cave? Upon his return, the enlightened man would metaphorically (and literally) be entering a world of darkness yet again and would be faced with the other unreleased prisoners. Others there would ridicule him for taking the useless ascent out of the cave in the first place. They could not understand something they have yet to experience, so what leadership can the man provide for he alone would be conscious of goodness?

It’s at this point that Plato describes the philosopher kings who have recognized the Forms of Goodness as having a duty to be responsible leaders and to not feel contempt for those who don’t share such enlightenment.

But, one person's power of enlightenment could encourage a few prisoners to risk emerging from the cave and the deceit therein. As numbers grow, confidence builds and shadows on the wall diminish.

Socrates finally concludes by likening this allegory to the Metaphor of the Sun in his work, The Republic. The sun is the source of "illumination", arguably intellectual illumination, which he held to be The Form of the Good, which is sometimes interpreted as Plato's notion of God. The metaphor is about the nature of ultimate reality and how knowledge is acquired.

"At all events, this is the way the phenomena look to me: in the region of the knowable the last thing to be seen, and that with considerable effort, is the idea of good; but once seen, it must be concluded that this is indeed the cause for all things of all that is right and beautiful – in the visible realm it gives birth to light and its sovereign; in the intelligible realm, itself sovereign, it provided truth and intelligence – and that the man who is going to act prudently in private or in public must see it" --Plato

After "returning from divine contemplations to human evils," Plato concludes

"A man is graceless and looks quite ridiculous when – with his sight still dim and before he has gotten sufficiently accustomed to the surrounding darkness – he is compelled in courtrooms or elsewhere to contend about the shadows of justice or the representations of which they are the shadows, and to dispute about the way these things are understood by men who have never seen justice itself."

No comments:

Post a Comment