Analysis Of Baseball

|

It's about Bat waits Ball fits It's about By May Swenson |

The Lucasville Historical Society posted a very interesting article about a baseball game between Lucasville and Vanceburg as originally reported in September 28, 1895. The detail, complete with the box score, is amazing. It offers an intimate look back at the “National Pastime” – a term first linked to baseball in print as far back as 1856. At that time, baseball was growing in popularity across the country and was played by people of all ages and just about anywhere the game could be played.

The historical society article made me think about what baseball was like in its earlier days. So, I decided to explore that topic. The content in this entry is mainly about Major League Baseball (in the National League) as it was played in 1895 although the 1890s is addressed. I hope you enjoy this small peek at MLB at the turn of the 20th century.

Baseball News Of 1895?

Cleveland Spiders

In the National League, there was big news about the Cleveland Spiders. That's right, not the controversially named “Indians” or the new “Guardians,” but the “Spiders” – a moniker that predates both mascots. The name “Spiders” itself emerged early in the team's inaugural NL season of 1889, owing to new black-and-gray uniforms and the skinny, long-limbed look of many players (thereby evoking the spider arachnid).

(David L. Fleitz. Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders.” Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2017.)

Allow me to digress (even further) …

The Spiders competed at the major league level from 1887 to 1899, first for two seasons as a member of the now-defunct American Association (AA), followed by eleven seasons in the National League (NL). Amid seven straight winning seasons under manager Patsy Tebeau, the team finished second in the National League three times – in 1892, 1895, and 1896. Six Spiders players were later inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including left fielder Jesse Burkett and pitcher Cy Young.

Spiders outfielder Louis Sockalexis played for the team during its final three seasons and is often credited as the first Native American to play major league baseball. Cleveland has long cited Sockalexis as the inspiration for their controversial former team name – "Indians" – though that claim is disputed.

But a dubious claim to fame came in 1899 when the Spiders finished the season 20–134 – 84 games behind the pennant-winning Brooklyn Superbas and 35 games behind the next-to-last (11th) place Washington Senators – a record which remains the worst for a single season in MLB history. Their batting records were the worst in the league in runs, hits, doubles, triples, home runs, walks, stolen bases, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage.

(“1899 Cleveland Spiders Statistics.” Baseball Reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/CLV/1899.shtml.)

Getting back to 1895 – in 1895, the Spiders again finished second, this time to the equally rough-and-tumble Baltimore Orioles. Cy Young again led the league in wins, and speedy left fielder Jesse Burkett won the batting title with a .409 average. The Spiders won the Temple Cup, an 1890s postseason series between the first- and second-place teams in the NL. Amid fan rowdyism and garbage-throwing, the Spiders won four of five games against Baltimore, including two wins for Cy Young.

The 1895 championship was the high-water mark for the franchise. The following season, Baltimore and Cleveland again finished first and second in the NL, but in the battle for the 1896 Temple Cup, the second-place Spiders were swept in four games. In 1897, despite a winning record, the franchise finished fifth, a season highlighted by Young throwing the first of three career no-hitters on September 18. The Spiders again finished fifth in 1898.

How about this story involving the Spiders from 1895? Before a game with the visiting Cleveland Spiders, the entire Chicago Colts team was arrested for "inciting, aiding and abetting the forming of a noisy crowd on a Sunday.” Reverend W.W. Clark and the "Sunday Observance League" had protested the concept of baseball on Sunday and instigated the police action. After owner Jim Hart posted bail, 10,000 fans remained to watch the "wanted men" beat the visitors 13-4.

(Year In Review: 1895 National League. Baseball Almanac. https://www.baseball-almanac.com/yearly/yr1895n.shtml.)

Historical Note:

The Cleveland Spiders were heavily plundered and sent to the St. Louis Perfectos by the Robison brothers – who owned both teams – and what was left of the Spiders was so awful, their fans literally stopped coming out to root for them.

And when they stopped coming out – the Spiders drew just 6,088 spectators over 31 home games – the Robisons simply had the Spiders play their second half schedule almost entirely on the road. Cleveland lost 39 of its last 40 games, was outscored in its last nine (all losses), 111-22, and finished the year with a 20-134 mark that would make the 1962 New York Mets look respectable by comparison.

(“1900: On the Brink of Adulthood. “https://thisgreatgame.com/1900-baseball-history/. The Online Book of Baseball.)

A Sad Day In Cincy

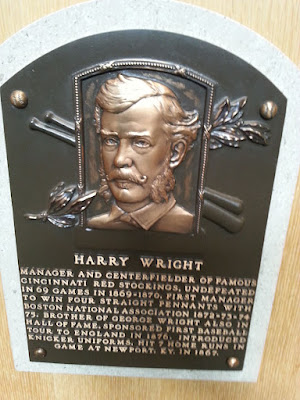

In 1895, there was some very sad news on the Cincinnati Reds front. William Henry "Harry" Wright was an English-born American professional baseball player, manager, and developer. He died on October 3, 1895, after contracting a serious illness in his lungs.

Sportswriter Henry Chadwick wrote of Wright's passing: “No death among the professional fraternity has occurred which elicited such painful regret.” In fact, the Society for American Baseball Research revealed a 1999 poll of its members that rated Wright as the third greatest contributor to 19th century baseball.

Harry Wright assembled, managed, and played center field for baseball's first fully professional team, the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings. Wright is credited with introducing innovations such as backing up infield plays from the outfield and shifting defensive alignments based on hitters' tendencies. He also adapted bowling techniques from cricket to become an effective pitcher known for his off-speed pitches that differed from most of the hard-throwing pitchers of the day. He would later use this to relieve fireballer Asa Brainard effectively and thus institute the strategy of relief pitching.

For his contributions as a manager and developer of the game, Wright was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953 by the Veterans Committee. Wright was also the first to make baseball into a business by paying his players up to seven times the pay of the average working man.

Born in Sheffield, England, he was the eldest of five children of professional cricketer Samuel Wright and his wife, Annie Tone Wright. His family emigrated to the U.S. when he was nearly three years old, and his father found work as a bowler, coach, and groundskeeper at the St George's Cricket Club in New York. Harry dropped out of school at age 14 to work for a jewelry manufacturer, and worked at Tiffany's for several years.

Both Harry and George, 12 years younger, assisted their father, effectively apprenticing as cricket "club pros". Harry played against the first English cricket team to tour overseas in 1859.

Both brothers played for some of the leading clubs during the amateur era of the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP). In 1863, his Knickerbocker club all but withdrew from official competition, and Wright joined Gotham of New York, primarily playing shortstop.

Then, in 1865, he left for Cincinnati, eventually abandoning cricket for baseball When the NABBP permitted professionalism for 1869, Harry augmented his 1868 imports (retaining four of five) with five new men, including three more originally from the East.

No one but Harry Wright himself remained from 1867; one local man and one other westerner joined seven easterners on the famous First Nine. The most important of the new men was brother George, probably the best player in the game for a few years, the highest paid man in Cincinnati at $1400 for nine months. George at shortstop remained a cornerstone of Harry's teams for ten seasons. The team became known as the Red Stockings – baseball's first openly all-professional team.

1895 Cincinnati Red Stockings Emblem

(Greg Rhodes. "June 14, 1870: The Atlantic Storm: Red Stockings suffer first defeat". Society for American Baseball Research.)

As the first salaried club, Cincinnati also precipitated great controversy over the institution of professionalism. Any mingling of money with the game at that point was regarded as a recipe for corruption and the attraction of carousing undesirables, which would spell doom for the game.

However, the Red Stockings were perhaps the most disciplined team ever to attract such attention, as demanded by manager, center fielder, and executive Harry Wright: Wright’s reputation as the most ethical gentleman in the game – “There was no figure more creditable to the game than dear old Harry,” said The Sporting News – defied the money-grubbing stereotype of what an exponent of professionalism was supposed to be.

Instead, Wright emphasized the necessity of fair play and high ethical standards for the advancement of the game, an admonition that he heeded as well. In one 1868 home game, he reversed the blatantly errant ruling of an umpire seeking to curry the favor of the Cincinnati crowd. Owing largely to this action, the Red Stockings went on to lose the game. In later years Wright himself was entrusted to umpire games within his own league.

The club dropped professional baseball after the second season, its fourth in the game. As it turned out, the Association also passed from the scene.

Historical Note:

In 23 seasons of managing in the National Association and National League, Wright's teams won six league championships (1872–1875, 1877, 1878). They finished second on three other occasions, and never finished lower than sixth. Wright finished his managerial career with 1,225 wins and 885 losses for a .581 winning percentage. He was the first manager to reach one thousand wins as a manager.

Harry Wright was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1953 by the Veterans Committee, much later than his brother (1937), and much longer than many thought that he should have had to wait. Today, Wright strikes historians as, in the words of Bruce Markusen, an “especially underrated Hall of Famer.” Popularly regarded in his time as “The Father of Professional Baseball,” Wright’s modern legacy pales in comparison, though many of his innovations characterize the game that we know today.

(Christopher Devine. “Harry Wright." https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/harry-wright/. Society For American Baseball Research.)

The lawless environment of 19th Century baseball is illustrated to (slightly) exaggerated effect in this Sporting Life commentary at left. The turn of the century provided little hope of improvement as a monopolistic and near-corrupt National League blindly trudged on. (The Rucker Archive [inset], Library of Congress)

What Was a National League Game Like In 1895?

To quote The Online Book of Baseball: “The 19th Century history of baseball reads like the first 20 years of a young person’s life, growing up, evolving, learning, misbehaving. Though the game exploded on a recreational level in the decades before the Civil War, the birth of the sport remains virtually untraceable.”

(“1900: On the Brink of Adulthood. “https://thisgreatgame.com/1900-baseball-history/. The Online Book of Baseball.)

The 1890s were a period of significant change in baseball, in terms of leagues, teams, rules and offensive levels By the end of the decade, we had a game that is very similar to modern-day baseball, a far cry from the 1880s.

The decade began with the formation of a third major league, the Players League, by the Brotherhood, in an attempt to fight the power of the owners. While it was the top league in term of talent, it lasted only one year before folding in a year of poor economic performance for all three major leagues. The fading American Association collapsed after the next season. That left a 12-team National League as the sole major league for the rest of the decade. To try to liven things up, the Temple Cup was introduced as a postseason series, but it was never taken very seriously and was gone by the end of the decade.

Historical Note:

The Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players (or simply Brotherhood) represented the first serious effort to organize a labor union consisting of baseball players. It was launched in 1885 through the efforts of star player John Montgomery Ward, who was also a lawyer, with the aim of raising player salaries in recognition of the growing popularity of professional baseball and the growth in revenues generated by the game.

(“Baseball Reference.” https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Brotherhood_of_Professional_Baseball_Players.)

Rosters (No Subs, Just Play)

During this early era, the rules of the sport for many years prohibited substitution during games except by mutual agreement with opponents, and the role of a team manager was not as specifically geared toward game strategy as in the modern era; instead, managers of the period combined the role of a field manager with that of a modern general manager in that they were primarily responsible for signing talented players and forming a versatile roster, as well as establishing a team approach through practice and game fundamentals.

Rule 15

This was a timely and kindly reminder for players of the game as stated in Playing Rules For the National League of Base Ball Clubs, Adopted December 17, 1889:

“Each player shall be required to present himself upon the field during said game in a neat and cleanly condition, but no player shall attach anything to the sole or heel of his shoes other than the ordinary base ball shoe plate.”

Pitcher's Plate

Major changes were instituted for the 1893 season. The pitcher's box was removed and replaced with a whitened rubber "Pitcher's Plate," that measured 12 inches (third to first) by 4 inches and was even with the surface. The back of the pitcher's plate was centered on an imaginary line drawn from the intersection of the third and first base foul lines to the center of second base. The new pitching distance, 60 feet 6 inches, was measured from the front of the pitcher's plate to the intersection of the third and first base foul lines.

In 1895 the pitcher's plate was size was increased in length (third to first) from 12 inches to 24 inches and in width from 4 inches to 6 inches.. The pitcher's position did not change for the rest of the 19th century. It is extremely important to note that all pitching in the 19th century was done from a flat surface. The "pitcher's mound" would not make its debut until the 20th century.

(Eric Miklich. “The Pitcher's Area.”19c Baseball. http://www.19cbaseball.com/field-8.html.)

Strikes and Foul Balls (Did You Do It On Purpose?)

A strike was defined as:

A ball struck at and missed by the Batsman without its touching his bat.

A ball legally delivered by the Pitcher that does not pass below the knee and above the shoulder and over Home Base, but not struck at by the batsman.

An obvious attempt to make a foul hit.

The third rule is technically the beginning of the foul batted ball strike. It was not consistent as the umpire had to make a judgment call when he felt that it was done intentionally and every umpire would view those instances in a different manner.

Walks (Unsportsmanlike Behavior)

A “walk” was instiuted in 1863, originally as a sort of unsportsmanlike-conduct penalty: "Should the pitcher repeatedly fail to deliver to the striker fair balls, for the apparent purpose of delaying the game, the striker shall be entitled to the first base.” Then, that rule gave the pitcher 9 “balls.”

In 1880, the National League changed the rules so that eight "unfair balls" instead of nine were required for a walk. In 1884, the National League changed the rules so that six balls were required for a walk.

And, in 1887, the National League and American Association agreed to abide by some uniform rule changes, including, for the first time, a strike zone which defined balls and strikes by rule rather than the umpire's discretion, and decreased the number of balls required for a walk to five. In 1889, the National League and the American Association decreased the number of balls required for a walk to four.

(2001 Official Major

League Baseball Fact Book. St. Louis, Missouri: The Sporting

News. 2001.)

Game at League Park, Cincinnati in 1890s

Home Runs – “Out Of the Park?”

In the early days when the ball was less lively and the ballparks generally had very large outfields, most home runs were of the inside-the-park variety. The first home run ever hit in the National League was by Ross Barnes of the Chicago White Stockings (now known as the Chicago Cubs), in 1876.

The home "run" was literally descriptive. Home runs over the fence were rare, and only in ballparks where a fence was fairly close. Hitters were discouraged from trying to hit home runs, with the conventional wisdom being that if they tried to do so they would simply fly out. This was a serious concern in the 19th century, because in baseball's early days a ball caught after one bounce was still an out. The emphasis was on place-hitting and what is now called "manufacturing runs" or "small ball.”

Not until the National League and American Association of Base Ball Club written rules, in 1889, was this issue of a ball hit over the fence addressed. The rules stated that any fair ball hit out of the field of play less than 210 feet from home base was only a double. The distance was changed to 235 feet for the 1892 season.

No player led the National League with double digit home runs in the 1870s. In the 1880s, 14 players, counting 19 seasons from three leagues, captured the home run title with 10 or more home runs.

During the 1890's, only one time did a player lead his league in home runs with less than 10. That occurred in 1890 in the American Association. In 14 seasons and four leagues in the 1890's, only four times did a player lead the league in home runs with less than 13. Certainly the balls were made better and the hitters were starting to gain an advantage over the pitchers.

(Eric Miklich. “The Home Run.” 19c Baseball. http://www.19cbaseball.com/field-6.html.)

Top: A vintage reproduction of a circa 1906 “mushroom” bat, designed to provide a counterweight to the early heavy bats that could weigh up to 50 oz. Bottom: Vintage reproduction of a “Lajoie” bat designed by Napoleon “Nap” Lajoie.

Bats

The National League made two major changes for 1885. It became legal to have 18 inches of the handle wrapped in twine and one side of the bat was allowed to be flat. The American Association adopted this rule when they followed the same rules as the National League in 1887.

In 1893, the second season of the National League and American Association of Base Ball Clubs, the bat was no longer allowed to be flat on one side but was required to be round. The length was still limited to 42 inches and the thickness of the thickest part was still two and on-half inches. The thickness of the bat was increased to two and three-quarters inches in 1895 and remains the same today – a touch longer than regulation softball bats.

Patent No. 430,388 (June 17, 1890) awarded to Emile Kinst for an “improved ball-bat.” In his patent, Kinst wrote: “The object of my invention is to provide a ball-bat which shall produce a rotary or spinning motion of the ball in its flight to a higher degree than is possible with any present known form of ball-bat, and thus to make it more difficult to catch the ball, or if caught, to hold it, and thus further to modify the conditions of the game….”

Historical Note:

Generally, early bats tended to be much larger and much heavier than today’s. The thinking was that the bigger the bat, the more mass behind the swing, the bigger the hit. And without any formal rules in place to limit the size and weight of the bat, it wasn’t unusual to see bats that were up to 42 inches long (compared to today’s professional standards of 32-34) with a weight that topped out at around 50 ounces (compared to today’s 30).

In 1884, the most famous name in baseball bats made its debut when 17-year-old John A. “Bud” Hillerich took a break from his father’s woodworking shop in Louisville, Kentucky, to slip away and catch a Louisville Eclipse game. When the team’s slumping star Pete Browning broke his bat, the young Hillerich offered to make him a new one. Bud made a new bat to Browning’s specifications, and the next game, the star of the Louisville Eclipse broke out of his slump, shining brightly once again, and the Louisville Slugger was born.

Gloves

The glove started out as merely a leather work glove, with or without full fingers, and progressed to a more padded piece of equipment. It is impossible to pinpoint the first player to wear a "glove" but there have been reports as early as 1860 that catchers were wearing them. It would seem that the first baseman would be the next position player to don a "glove."

In 1885, Providence Grays shortstop Arthur Irwin, while attempting to protect two broken fingers, added "padding" to a buckskin glove. This may be the first instance of a player introducing noticeable padding to a glove.

Also in 1895, responding to the complaints of senior citizens like Cap Anson, the National League the league restricted the size of gloves for all fielders, except catchers and first basemen, to 10 ounces, with a maximum circumference of 14 inches around the palm. They also rescinds the rule forbidding intentional discoloring of the ball, thus allowing players to dirty the baseball to their satisfaction.

This would be the rule for the rest of the 19th century. Also in 1895, Cincinnati Reds second baseman Bid McPhee, the last of the bare-handed players, opened the season on April 16, wearing a glove.

Historical Note:

Anson was regarded as one of the greatest players of his era and one of the first superstars of the game. He spent most of his career with the Chicago Cubs franchise (then known as the "White Stockings" and later the "Colts"), serving as the club's manager, first baseman and, later in his tenure, minority owner. He led the team to six National League pennants in the 1880s. Anson was one of baseball's first great hitters, and probably the first to tally over 3,000 career hits.

His contemporary influence and prestige are regarded by historians as playing a major role in establishing the racial segregation in professional baseball that persisted until the late 1940s. On several occasions, Anson refused to take the field when the opposing roster included black players. Anson may have influenced the most noted vote in 19th-century professional baseball in favor of segregation: one on July 14, 1887 by the high-minor International League to ban the signing of new contracts with black players.

Right after the vote, the sports weekly Sporting Life stated, “Several representatives declared that many of the best players in the league are anxious to leave on account of the colored element, and the board finally directed Secretary [C.D.] White to approve of no more contracts with colored men.”

("Fantasy Baseball: The Momentous Drawing of the Sport's 19th-Century 'Color Line' is still Tripping up History Writers.” The Atavist, June 14, 2016.)

Anson acted in ways that would not be tolerated today. One was the relative freedom a captain had in his day to argue with the usually lone umpire. Also, starting in the latter 1880s, he often bet on baseball, mainly on his team's chances to win the pennant. In that era, the big taboo was for players to take bribes to purposely lose games. Betting by players, managers, and owners was regarded as acceptable so long as they did not bet against their team doing well or associate with gamblers.

(Howard W. Rosenberg. Cap Anson 4: Bigger Than Babe Ruth: Captain Anson of Chicago. Tile Books. p. 560. 2006.)

Catcher's Mask

The catcher's mask may have been first worn by Jim Tyng of the Harvard University Base Ball Club in an exhibition game loss against the Boston Red Stockings in May of 1876, 7-6. Tyng's roommate and team Captain, Fred Thayer, is said to have "invented" the mask in 1875. Thayer modified a fencing mask which enabled Tyng to move closer to home base and receive the ball without fear of being struck in the face.

Photo: Laced-Front Detachable Sleeves Baseball Jersey

Uniforms

The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club introduced the first "uniform" on April 24, 1849. The uniforms consisted of long blue woolen trousers, leather belts, white flannel shirts with a full collar and straw hats. At the end of the 1850's, many teams adopted the flannel shirt with the button on shield style, which contained the team's emblem, name or both.

The full length "pantaloon" pants were in vogue throughout the 1860s but presented a problem of having players getting their feet caught on the legs of the pants when running. Players used to wrap them tight to their shins and use tape or a small belt to hold them flush.

The 1868 Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first team to wear knickers. These "cricket-style" pants were less restrictive, and as a result their stockings or socks were now visible. Their red stockings became their trademark.

Many teams required that there players wear ties and usually it was a bow tie. The late 1870s also brought about the laced-front shirt style. (Some with detachable sleeves that eliminated the need for multiple jerseys of different sleeve lengths, allowing players to dress comfortably, whatever the weather conditions.)

Every team experimented with its own look. In came checkers, introduced in 1889 by the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. The New York Giants wore purple-lined baseball uniforms, the Kansas City Athletics in 1863 donned gold and green.

Historical Note:

Here's an interesting twist. With the emergence of the American Association, the National League made a league wide uniform decision at its annual meeting in Chicago on December 9, 1881. They did not want to be outdone by the new league who instituted a uniform code. Each team was to have multi-hued silk uniforms, with each shirt color representing a position on the field. The National League mandated that all players were to wear white pants, white belts and white ties. The shirts and hats represented the position they played.

Pitchers - Light Blue

Catchers - Scarlet

First Basemen - Scarlet and white vertical stripes

Second Basemen - Orange and black vertical stripes

Third Basemen - Blue and white vertical stripes

Shortstops - Maroon

Left fielders - White

Center fielders - Red and black vertical stripes

Right fielders - Gray

1st substitute - Green

2nd substitute - Brown

Socks (Defining Attire)

Baseball players have been displaying their socks since the Cincinnati Red Stockings decided it would look good in 1868. The team’s owner was said to have conceived the look partly to attract ladies to the games. It didn't take long for other teams to follow suit. After all, it offered a sophisticated look, much like that of cricket players.

The socks players wore were ordinary knee socks until 1905, when a Cleveland player named Nap Lajoie came down with blood poisoning after a spiking. The theory was that the dye in his socks entered his bloodstream, causing the illness.

Back then, it was commonly believed that the semi-permanent dye used to color the socks posed a risk for blood poisoning should the player received an injury with an open wound. To protect themselves, players wore white socks, known as sanitary socks, against their skin, which they covered with the colorfully dyed stirrup sock.

(Aiza Leano. “The History of Baseball Socks.” https://www.mksocks.com/blogs/news/the-history-of-baseball-socks. February 26, 2020.)

As more teams joined the league during the late 1800s, this demarcation of socks became standard protocol. While at the time each player wore a different color position-dependent uniform, the entire team had a designated sock color that remained constant.

At one point, the teams were only identified by their socks (maybe why socks became indicative of team names).

National League team color socks:

Boston Red Caps- Red

Buffalo Bisons - Gray

Chicago White Stockings - White

Cleveland Blues - Navy

Detroit Wolverines - Old Gold

Providence Grays - Light Blue (sky)

Troy Trojans - Green

Worcester Ruby Legs - Brown

American Association team color socks:

Baltimore Orioles - Yellow

Cincinnati Red Stockings- Red

Louisville Eclipse - Gray

Philadelphia Athletics - White

Pittsburgh Alleghenys - Black

St. Louis Browns - Brown

By 1905, the traditional sock had evolved and players from every team were opting for the new and more colorful baseball stirrup socks.

(“Evolution of Baseball Equipment.” 19c Baseball. http://www.19cbaseball.com/equipment-2.html.)

Cleats

Spiked shoes were also used by many players in the 1860s and the shoe plate (cleat), worn under the heel and toe was introduced in the late 1870s. The shoes were usually black, but could be white or white with tan accents.

The first all-leather shoe made available by Spalding was the calf skin “League Club Shoe,” first offered in 1882 for $6 per pair. By the end of the decade, Spalding had introduced an all-Kangaroo leather shoe available for $7 per pair.

Though it is likely that no spikes were used on the earliest baseball shoes, by the late 1860s spikes similar to those found on modern golf shoes were used by top-flight players. The spikes were removable and a complete set cost $1.50.

What are now recognized as the more traditional metal baseball cleats, the tri-cornered shoe plates worn under the toe and the heel, were first introduced in the 1870s. These steel-plate cleats were much less expensive (30 cents per pair when first advertised by Spalding) than the individual spikes and, according to the Spalding Base Ball Guide of 1880, “the majority of professional baseball players use these plates both on the heel and the toe.”

The introduction of the shoe plate signaled the demise of individual spikes, but it was not until 1976 that the baseball rulebook explicitly outlawed spikes such as those found on golf and track shoes from the baseball field.

(“Dressed To the Nines: A History Of the Baseball Uniform.” http://exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org/dressed_to_the_nines/shoes.htm.)

A Ballad of Baseball Burdens

By Franklin Pierce Adams

The burden of hard hitting. Slug away

Like Honus Wagner or like Tyrus Cobb.

Else fandom shouteth: “Who said you could play?

Back to the jasper league, you minor slob!”

Swat, hit, connect, line out, get on the job.

Else you shall feel the brunt of fandom’s ire

Biff, bang it, clout it, hit it on the knob—

This is the end of every fan’s desire.

The burden of good pitching. Curved or straight.

Or in or out, or haply up or down,

To puzzle him that standeth by the plate,

To lessen, so to speak, his bat-renoun:

Like Christy Mathewson or Miner Brown,

So pitch that every man can but admire

And offer you the freedom of the town—

This is the end of every fan’s desire.

The burden of loud cheering. O the sounds!

The tumult and the shouting from the throats

Of forty thousand at the Polo Grounds

Sitting, ay, standing sans their hats and coats.

A mighty cheer that possibly denotes

That Cub or Pirate fat is in the fire;

Or, as H. James would say, We’ve got their goats—

This is the end of every fan’s desire.

The burden of a pennant. O the hope,

The tenuous hope, the hope that’s half a fear,

The lengthy season and the boundless dope,

And the bromidic; “Wait until next year.”

O dread disgrace of trailing in the rear,

O Piece of Bunting, flying high and higher

That next October it shall flutter here:

This is the end of every fan’s desire.

ENVOY

Ah, Fans, let not the Quarry but the Chase

Be that to which most fondly we aspire!

For us not Stake, but Game; not Goal, but Race—

THIS is the end of every fan’s desire.

No comments:

Post a Comment