Jesse Grant Tannery, Georgetown

Ulysses S. Grant

(born Hiram Ulysses Grant) is known for his accomplishments as a

Union General in the Civil War and, of course, for his presidency.

What is little known is that the Grant family were stalwarts in the

movement for the abolition of slavery. The story of Jesse, Ulysses'

father, provides insight into local history and is a touchstone to

the all-important freedom movement.

Ulysses'

childhood occurred in the middle of a seventy-year span of

Underground Railroad history. As early as the 1790s, families moved

to what became Ohio and aligned their homes to help liberate slaves.

Religious convictions played a big part. In southwestern Ohio,

certain Quakers, Calvinists, and Presbyterians worked together in

secrecy to develop liberation plans. Communities were often loose but

connected considering the times. (Jesse was a member of the Methodist

faith – also well-represented in the anti-slavery population.)

Four

years before their revival at Cane Ridge, the Presbyterian Church's

highest governing body, the General Assembly, directed people to

pray to redeem the frontier from “Egyptian darkness” so named for

Moses' struggle against Egypt's Pharaoh. In Buckeye

Presbyterianism, E.B.

Welsh describes the ministers serving the antislavery churches

surround Ulysses.

“In the southern part of the

state, especially in Chillicothe Presbytery, … convinced anti

slavery men were apparently in the majority, certainly the more

vocal. … most of them were from the South, several from the

Carolinas – such men as James Gilliland and William and James

Dickey, as well as John Rankin of Tennessee, men who had migrated to

this free staate of Ohio for the express purpose of getting their

families away from the blight and curse of slavery. With William

Williamson of Manchester, Samuel Crothers of Greenfield and Dyer

Burgess of West Union and later Rocky Spring, they brought the issue

before Presbytery again and again.”

(E.B. Welsh. Buckeye

Presbyterianism. 1968.)

Jesse Grant

Jesse Grant's paternal ancestor,

Matthew Grant, and wife Priscilla and their infant daughter, embarked

from Plymouth, England aboard the Mary and John with a party

of 140 emigrants who had been gathered chiefly from South West

England. It was one of many Pilgrims of the Puritan movement that

fled England to escape religious persecution. After a 70-day journey

the party arrived at Massachusetts Bay coloy in Nantasket, on May 30,

1630, and soon moved to and settled in Windsor, Connecticut.

Matthew was a

trusted member of the community. He became a surveyor and a town

clerk. Jesse's grandfather Noah Grant, and his brother Solomon,

fought and died in the French and Indian War, and his son, (Jesse's

father) also named Noah, served in the American Revolution, including

the Battle of Bunker Hill, soon advancing to the rank of captain.

Later generations migrated into Pennsylvania.

Ulysses'

father, Jesse Root Grant, was born in 1794 in western Pennsylvania,

to Noah and Rachel Kelly Grant. Noah Grant, was married to his first

wife, Anna Richardson, who became the parents of two children,

Solomon and Peter Grant. Upon Noah's return from service in 1787 Anna

died. On March 4, 1792, at Greensburg, Westmoreland County,

Pennsylvania, Noah married his second wife, Rachael Kelly, who became

Jesse's mother with the birth of her first born child on January 23,

1794. Noah named Jesse after the Honorable Jesse Root, Chief Justice

of the Superior Court of Connecticut.

In 1799, when Jesse was age five, Noah

moved his family to East Liverpool, and again in 1804, to Deerfield,

both in Ohio. Noah worked in a shoe shop, earning a modest wage in

Greensburg.

Jesse's mother, Rachel, died the spring

after Jesse turned eleven, and her death scattered the family. For a

time Jesse lived with Sallie Isaac Tod, whose husband was an Ohio

judge. (Their son would be Ohio's governor during the Civil War.)

According to biographer G.L. Corum, “in motherless Jesse, Mrs. Tod

helped the young teen acquire a basic education and infused him with

a love of reading. Jesse also credited her with his decision to

become a tanner.”

Jesse Grant moved to Point Pleasant in

1820 and found work as a foreman in a tannery owned by his

half-brother Owen Brown (father of the famous John Brown who led the

raid at Harpers Ferry). Owen was a stout and outspoken abolitionist

and Jesse often listened to his public orations against slavery,

where he became familiar with and supportive of the cause. During

this time Jesse lived under the same roof as John Brown, became

friends and came to know his abolitionist philosophy.

Later in life Jesse would describe John Brown as "a man of great

purity of character, of high moral and physical courage, but a

fanatic and extremist in whatever he advocated." Harold

I. Gullan, in his book, Faith

of Our Mothers,

mentioned that Jesse Grant moved to Ravenna, Ohio “because he hated

slavery” [in Kentucky].

Jesse soon met his future wife, Hannah,

and the two were married on June 24, 1821. Ten months later Hannah

gave birth to their first child, a son. At a family gathering,

several weeks later the boy's name, Ulysses, was drawn from ballots

placed in a hat. Wanting to honor his father-in-law, Jesse declared

the boy to be Hiram Ulysses, though he would always refer to him as

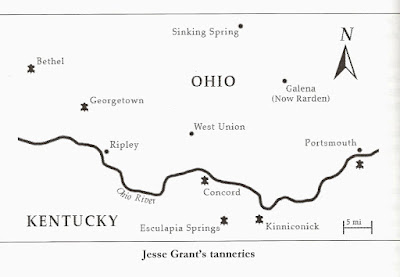

Ulysses. Jesse eventually gained ownership of many tanning

locations.

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law accelerated

vengeance against escaped slaves and those who assisted them. At that

time, Jesse Grant ran his interstate commerce sending animal hides,

tanning supplies, and leather goods between Ohio and Illinois. Corum

states, “He had tanneries on both sides of the Ohio River, with a

few extending down into Kentucky and a few more stretching up the

Mississippi.”

Jesse wrote about his tanneries …

“As tanning was absolutely

necessary to the support of a leather store, I set up my youngest

son, Orville, then about nineteen, in a new tannery of eighty vats,

in the chestnut oak bark region, twenty-four miles from Portsmouth,

Ohio, where we got plenty of bark delivered at three dollars per

cord. Soon after we bought another tannery of 130 vats, five miles

from Portsmouth, where bark cost five dollars. It was not long before

we bought still another tannery of 110 vats, in Kentucky, opposite

Portsmouth, and where bark cost about eight dollars. These tanneries

all employed steam power, but labor, bark, and hides advanced, so as

to make tanning rather unprofitable, and the Kentucky tannery has

been sold; the other two are still (being) run.”

(Jesse Grant. “Biological Sketches.” 12 No 8. September 24,

1868.)

He talked about tannery and not about

slavery, but in the woods halfway between Portsmouth and Sinking

Spring, Ohio, where no town existed, more went on.

Helen Christian in Echo of Rarden

History revealed the name Galena was adopted when the

first plat of the town was made on October 10, 1850. Orville Grant,

brother of Ulysses S., named the town for his home in Galena,

Illinois (“Galena” refers to a black mineral.)

Orville's new town coincided with

Congress passing the Compromise of 1850, containing the

ultra-controversial Fugitive Slave Law. Of course, the passage of

this law made abolitionists all the more resolved to put an end to

slavery. It appears the Grants doubled down on their underground

efforts. The timing, placement, and name of Galena, Ohio supports

this. It is known that the Grant family helped liberate slaves with

through their tannery operations.

Corum says, “Fleeing feet would have

headed north through the woods (now Shawnee Forest) to Galena, Ohio,

on their way to Sinking Spring. Ammen (newspaper editor) bragged

about helping more fugitives escape than anyone else, indicating he

received runaways from various lines.”

Corum believes Jesse was putting up a

smokescreen with talk about chestnut bark prices. His Underground

Railroad operation even extended into Kentucky – a wide expanse of

work for freedom. In Lewis County, Jesse operated a tannery. And,

eventually, Jesse even moved his family to Covington, Kentucky, where

they were better able to aid fugitives by operating on both sides of

the river. Indeed, his tanneries map a way out of slavery during

their operations.

Jesse died June 29, 1873, in Covington,

Kentucky, shortly after President Grant began his second term.His

funeral was held at the Union Methodist Episcopalian Church in

Covington. Jesse was buried at Spring Grove Cemetery, in Cincinnati,

Ohio. His wife, Hannah, died ten years later in 1883, in Jersey City,

New Jersey, just two years before their son Ulysses died.

Sources

“Jesse

Grant” (1794-1873)

http://presidentusgrant.com/picture-archives/1630-1822-ancestors-of-u-s-grant/jesse-grant-1794-1873/

Marshall,

Edward Chauncey (1869). The

ancestry of General Grant, and their contemporaries. Sheldon

McFeely,

William S. (1981). Grant:

A Biography.

Corum,

G.L. Ulysses Underground. 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment